In early 1953, many believed that the American scientist Linus Pauling would be the first to discover the structure of DNA. At the same time in Britain, three scientists- James Watson and Francis Crick at Cambridge, and Maurice Wilkins in London-were also attempting to determine DNA’s structure. Perhaps even they, stalled after their models repeatedly failed, thought Pauling might find the DNA structure first in January 1953.

Pauling, in his paper on DNA structure published in January 1953, proposed the same DNA model that Watson-Crick had already conceived in 1951 and knew was incorrect. Upon reading Pauling’s paper, Watson rushed to London to share the happy news with Wilkins.

Upon Arriving excitedly in London the next morning, Watson met Wilkins in his lab. They were discussing about what to do next and how to advance the search for DNA structure. It was then that Wilkins showed Watson a photo taken 8-months prior using X-rays by his colleague, Rosalind Franklin. Without seeking Rosalind’s permission, and without her knowledge, the drawer of her work desk had been rummaged through that day.

Rosalind, Who Suffered Injustice

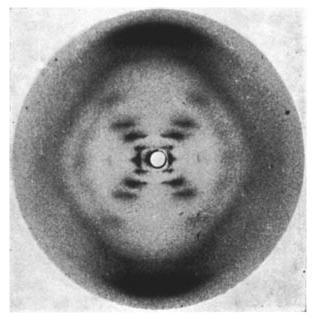

The photo Wilkins showed Watson on the afternoon of January 30, 1953, is what we now know as ‘Photo 51’. Though it might seem ordinary now, many things were hidden within the ‘X’ shape and the ‘streaks’ visible in Rosalind’s ‘Photo 51’.

Upon seeing the photo, it became clear to Watson that DNA is composed of two strands (double strand) in a helical form (double helix). Knowing this was a ‘Eureka moment’ for Watson and Crick. Watson, who rushed back to Cambridge to tell Crick after seeing the photo, later said somewhere, “The moment I saw that picture, my mouth fell open, and my pulse began to race.”

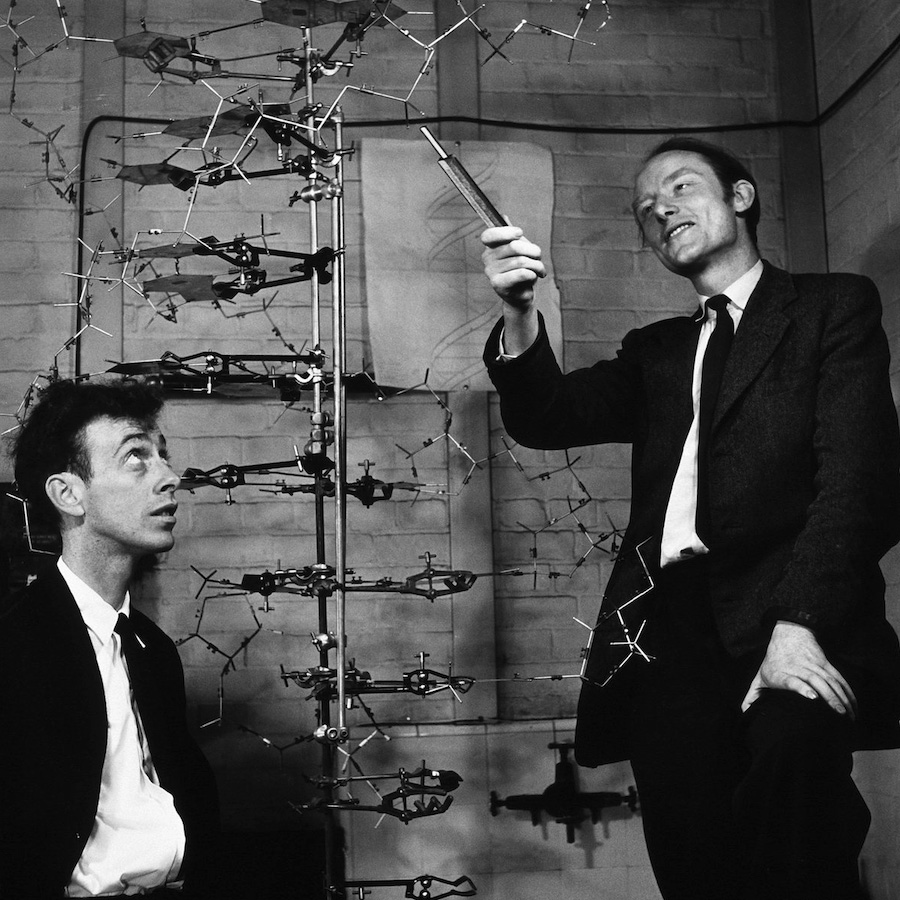

Based on that ‘Photo 51’, Watson-Crick resumed their DNA structure research two days later (from February 2). By March 7, they had already built the DNA model we recognize today. On April 25, their paper on the DNA discovery was published in ‘Nature’; the title was ‘Molecular Structure of Nucleic Acids.’

Rosalind, who took ‘Photo 51’, was forced out of King’s College London, where she worked, before the end of 1953, under the condition that she could never work on DNA again. Her ‘supervisor’ was none other than Wilkins. Many years later, while tagging Rosalind as the ‘Dark Lady of DNA,’ he reportedly said somewhere, “She was a quarrelsome unmarried woman, who couldn’t collaborate with others and couldn’t present her work with originality.”

Rosalind then went to Birkbeck College and spent four years (1954-1958) studying virus structure using X-rays. Working particularly on RNA viruses, she quickly determined the structures of the Tobacco Mosaic Virus and Polio virus.

Although she didn’t receive credit for the DNA ‘discovery’ until much later, modern virology gives her high credit; much virus research is still based on the work she did. Having always worked with X-rays, perhaps due to its effects, she was diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 1956 and passed away on April 16, 1958, at the age of 37.

Today, Watson and Crick are universally known as the scientists who discovered DNA. For this, all three, including Wilkins, received the Nobel Prize in 1961. The rule of not awarding the Nobel Prize to more than three people still exist, and the priority given to women, especially deceased ones, remains largely unchanged.

Watson and Crick merely built a model in 1953 showing what DNA looks like. Wilkins played a supportive role by providing further evidence for their model using the same X-ray methods. They did not discover what DNA looks like through their own lab work/experiments. They had only shown what the structure of DNA might be based on the studies of others.

This article will attempt to connect the research that preceded Watson-Crick in the quest for DNA structure, explaining how we arrived at the double-helix DNA we know today. It is noteworthy that Rosalind is not the only forgotten figure.

Research and Discovery

Tracing the quest for DNA takes us back to 1869. There was a Swiss scientist, Friedrich Miescher, not often remembered now. While researching proteins in white blood cells (WBCs), he found a strange kind of molecule. It was a molecule lacking sulfur, unlike proteins, but containing a lot of phosphorus, not found elsewhere.

Miescher named it ‘nuclein’ because it was found in the cell’s nucleus. The ‘nuclein’ he discovered then is what we know today as DNA. Miescher wrote about the nuclein he discovered, ‘Like proteins, nucleins might also come in many varieties.’

Science and history largely forgot Miescher’s research and ‘nuclein’ for a long time. However, starting in the early 1900s, nuclein began to be known as ‘nucleic acid’.

It was many years later after Miescher, Russian scientist Phoebus Levene investigated what nucleic acids contain. His ‘polynucleotide’ theory, proposed in 1919, first suggested that nucleic acids might be strands made of long chains (polynucleotide chains) of different nucleotides. Although Levene’s ‘tetranucleotide’ model about the sequence of nucleotides was later proven incorrect, his research during the early years of DNA discovery is still very significant.

Levene was the first to state that these nucleotides are composed of phosphate-sugar-nitrogen base units. Similarly, he was the first to show that there are two types of nucleic acids based on the difference in the pentose sugar (a five-carbon aromatic ring). He laid the foundation for understanding that DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid), found in the cell nucleus, and RNA (ribonucleic acid), found both inside and outside the nucleus, differ due to difference in a single oxygen atom.

Through the discoveries made by Levene and his contemporaries between 1920-1930, these different nucleotides gradually became known. It became clear that the nitrogenous bases within nucleotides differ. It was also known that nucleotides come in two types based on these nitrogenous base differences.

One type of nitrogenous base, purines, are made of two carbon-nitrogen rings and include Adenine-A and Guanine-G. The other type of nitrogenous base has only one carbon-nitrogen ring. Called pyrimidines, they are of three types: Cytosine-C, Thymine-T, and Uracil-U. While the other 3 nucleotides (A, G, C) are found in both, Thymine and Uracil differ between DNA and RNA. DNA contains Thymine (T), while RNA contains Uracil (U) instead.

The work of clearly dissecting the phosphate, sugar, and nitrogenous base within the nucleotide was done much later by Alexander Todd. In his 1940 paper, he stated that the phosphate-sugar-nitrogen base are arranged in a specific way, and, also showed how one nucleotide connects to another to form nucleotide chains (polynucleotide chains).

This connection of nucleotides, known as the phosphodiester bond, can be understood as follows: the fifth carbon of the sugar in one nucleotide connects to the third carbon of the sugar in the second nucleotide, and this sequence continues to form the polynucleotide chain. Based on this connection between two nucleotides in the strand, the DNA strand is understood to have a specific direction (5′-3′ or 3′-5′). He was the first to show that the DNA strand is formed by nucleotides linking one after another via phosphodiester bonds onto the sugar-phosphate backbone.

By the 1940s, much was known about what DNA/nucleic acid contained, but its function was still unknown.

Frederick Griffith was the first to investigate whether DNA performs the function of storing information, as we know today. In 1928, while working with bacteria, he observed that the ability to resist toxins (drug resistance) could be transferred from one bacterium to another, leading him to suspect that nucleic acid might do something similar.

Inspired by Griffith’s findings, Avery, MacLeod, and McCarty began working on this. In 1944, they were the first to show that DNA, not protein, stores all our information and traits. Their discovery, not widely believed at the time, had to wait another 8 years for strong proof.

In 1952, research by Martha Chase and Alfred Hershey on viruses proved that DNA is indeed the means of information storage. They observed that when bacteriophages (viruses that infect bacteria) attach to bacteria, only the virus’s DNA enters the bacteria, yet new bacteriophages are still produced. After observing similar behavior in other viruses, there was no longer any doubt that DNA, not protein, is the molecule that stores all information.

By the late 1940s, it was known that DNA is a long strand formed by the linking of four different nucleotides (A, T, G, C) in a chain, and that it transmits information. However, many things were still unknown, including how DNA strands are organized, whether it consists of a single strand or more than one strand.

Speaking of DNA strands, Erwin Chargaff must never be forgotten. Chargaff, who started researching DNA after reading Avery’s ’44 paper’, proposed a theory in 1950 that we now recognize as Chargaff’s rules: “In DNA, purines and pyrimidines exist in equal amounts, roughly half-and-half, and the amounts of all four nucleotide bases are also approximately equal (specifically A=T and G=C).”

This result, not limited to humans, hinted that perhaps multiple DNA strands are somehow joined together, complementing each other. He was the first to suspect that nitrogenous bases might be linked to each other in some way other than the phosphodiester bonds mentioned earlier.

Writing later about Avery, Chargaff reportedly said somewhere, “Avery gave us the first text of a new language, showed us where to look. I was able to discover it.” However, he couldn’t show how A and T or G and C are paired together (A-T, G-C).

How these nitrogenous bases complement each other and how the two strands are held together remained unknown; Watson-Crick provided the answer to that.

Linus Pauling, mentioned at the beginning, was another giant alongside Chargaff. Perhaps, few others have done as much work as he did on understanding how molecules and atoms are structured. He also discovered the ‘alpha helix’ structure of proteins. I read somewhere that he later expressed regret for not deeply focusing on DNA, as he was busy researching the cause of sickle cell anemia at the time.

He was the first scientist to suspect that because DNA strands and nucleotide bases are complementary, they can pass from one cell to another, from one generation to the next. Speculating about DNA replication, he said this in 1949: “The two parts, which are structurally complementary, each part can serve as a template for making the other part, and the combination of that template must replicate itself to create a new structure.”

Many thought Pauling would be the first to find the DNA structure. Watson and Crick also used to think so. Pauling only saw Rosalind’s ‘Photo 51’ much later. His DNA model was also born similarly [based on available data but missing key insights].

Watson, Crick, Rosalind, and Wilkins

After connecting everyone, we arrive at the four authors of the DNA paper published in April 1953. The order of authors was Watson, Crick, Wilkins, and Franklin & Gosling.

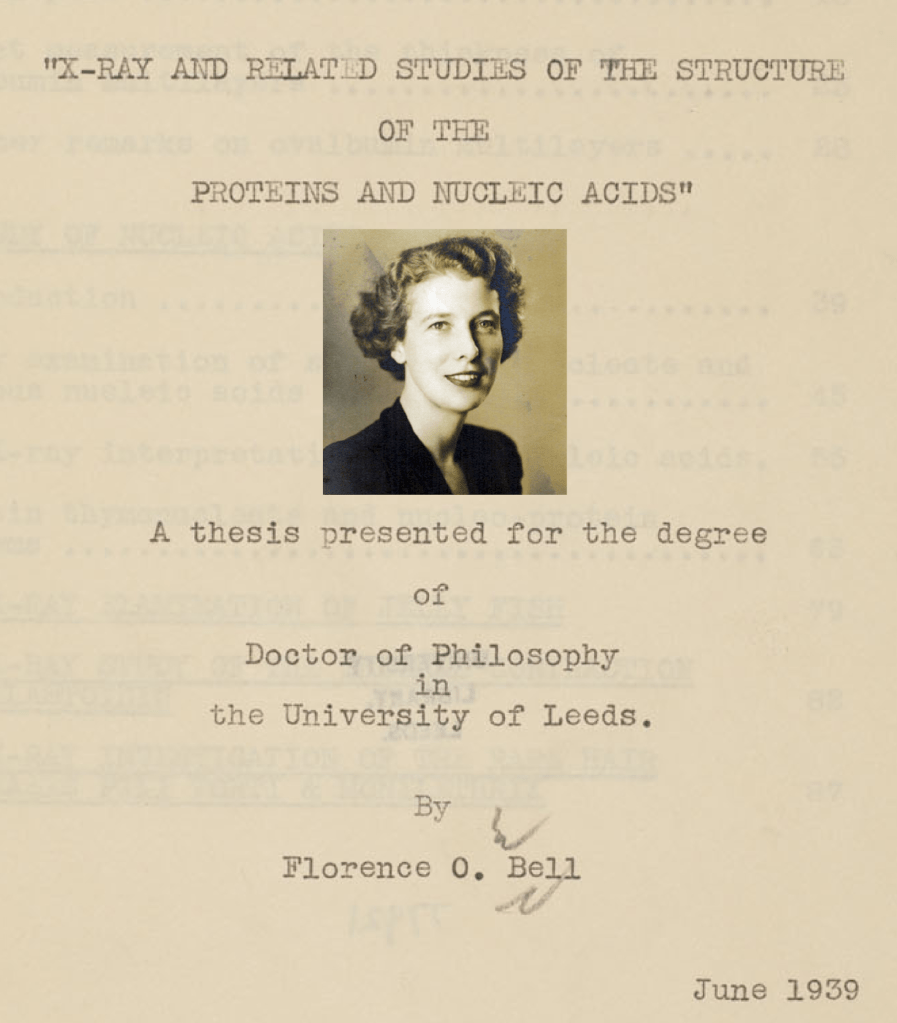

However, before connecting all of them, we cannot omit Florence Bell, another forgotten scientist who connects all four in the quest for DNA. Florence was among the early researchers studying DNA using X-ray photography.

It was seeing her Ph.D. work that prompted Wilkins to begin DNA research. Her X-ray photo included in her 1939 Ph.D. thesis showed that DNA must be made of a regularly repeating, organized structure, and for that reason, it differs from RNA. It was Florence who first showed that nucleotide bases are spaced 3.4 Angstroms (3.4 Å) apart and that DNA has a diameter of approximately 18.1 Angstroms (18.1 Å).

Florence concluded her 1939 Ph.D. thesis thus: “Discovering the chemical constitution of the gene is a great and necessary task for humankind. When we know that, the limits of our thought and understanding will expand so much that it’s unimaginable. Ultimately, we will find out what we are.”

In the process of improving her blurry photo, Rosalind and her ‘Photo 51’ emerged. Florence had also proposed a single-stranded DNA model in 1939, before it was known that DNA is double-stranded. World War II interrupted her work, and her thesis was not widely read at the time.

Among the few who read Florence’s thesis was Wilkins himself. Of the four key figures associated with the 1953 DNA papers, Wilkins was the first to work on DNA. After World War II, from 1945-46, he began taking X-ray photos of DNA at King’s College London using Florence Bell’s methods.

In early 1950, at some conference, Wilkins apparently showed the DNA X-ray photo he had taken. Because of the photo Wilkins showed, Watson, who had come to Europe from America for post-doctoral work, came to Cambridge in mid-1950 to work with him. After arriving in Cambridge, he met Crick. Crick was 12 years older than Watson, an unpopular graduate student, and had been assigned to the newly arrived researcher [Watson].

This is how Watson, Crick, and Wilkins met. The three began the search for DNA structure towards the end of 1950. Florence’s photo was not given much attention initially. They started building models in a room at Cambridge, trying to fit DNA nucleotide bases together like Lego bricks.

Their research paper, which came out at the end of 1951, also suggested the first model of DNA. It proposed that DNA has 3 strands, the central backbone is phosphate, and the nitrogenous bases face outwards, all base pairing with all bases.

Phosphates carry a significant negative charge. Placing phosphates together centrally caused problems with charge repulsion, repeatedly destabilizing the model. The added difficulty due to the incorrect atomic structures of two nitrogenous bases was also significant. It only became easier after Jerry Donohue corrected them in February 1953; I’ll connect that episode shortly.

Like Watson-Crick’s 1951 model, Pauling released his model in January 1953. Watson and Crick saw his DNA model, printed in America, on the evening of January 29th through Pauling’s son, who was studying at Cambridge. The next morning, Watson went to London to tell Wilkins, ‘Pauling also proposed a non-working DNA model just like ours.’

Photo 51

In Wilkins’ lab at King’s College, on cold London morning, they were discussing what to do next. Suddenly, Wilkins remembered the DNA photo taken nearly 8 months earlier by Rosalind, who worked with him. Rosalind was not in the lab that day. Wilkins searched the drawers of Rosalind’s work desk and found the ‘Photo 51’ she had taken. Upon seeing Rosalind’s ‘Photo 51’, Watson hurried back to Cambridge to tell Crick. Fearing Pauling might realize his mistake and correct it, they restarted their work just two days after finding ‘Photo 51’.

Rosalind Franklin had arrived at King’s College, where Wilkins worked, in 1950 on a 3-year fellowship in X-ray crystallography to work on proteins. Upon arrival, the college head assigned her to work on DNA. Wilkins always thought Rosalind was under his supervision, while Rosalind preferred to work independently.

Rosalind wasn’t the only scientist/researcher examining DNA with X-rays. At that time, the structure of DNA was unknown, so naturally, the existence of different DNA forms was not known either. Rosalind and her student Raymond Gosling were the first to discover that DNA exists in two different orientations (forms). They named these DNA forms ‘A’ and ‘B’.

Everyone who took X-ray photos of DNA before them had only managed to capture blurry images. Taking the photo took a long time, and during the process, the DNA would switch between ‘A’ and ‘B’ forms depending on the humidity. Rosalind and Gosling succeeded in controlling the humidity to isolate pure strands of DNA found in specific ‘A’ and ‘B’ forms and then took separate X-ray photos of the separated strands.

The ‘Photo 51’ they took was of the DNA ‘B-form’. Rosalind and Gosling took this photo on May 2, 1952, after nearly 60 hours of exposure. At that time, after taking the photo, there was no particular ‘Eureka moment’; others hadn’t seen it either. They then became busy searching for the ‘A-form’ of DNA, which is found more commonly than the ‘B-form’. They were still focused on that until early 1953. When Watson-Crick resumed work on DNA, they too had started working again (and published papers) on the DNA ‘B-form’, but it stalled as she left King’s college.

Rosalind’s ‘Photo 51’ made it possible to calculate the diameter (~20 Angstroms, Å) and pitch of the helix (~34 Å), the distance between two nucleotides (3.4 Å), and thus that there are 10 nucleotides per turn. ‘Photo 51’ also provided the basis for understanding that the four nucleotides are inside the sugar-phosphate backbone and are held together by base pairing with the other strand.

Wilkins showed that ‘Photo 51’ to Watson without Rosalind’s knowledge. She didn’t find out about it until much later. Shortly after she found out and protested, her fellowship was terminated, and the condition was imposed that she could never work on DNA again. Before 1953 ended, Rosalind was removed from King’s College, not even allowed to take her notes on DNA.

For Watson-Crick, Rosalind’s ‘Photo 51’, which Watson first saw on January 30, 1953, effectively unlocked a lock and key. Only after this did it become possible for Watson and Crick to show how these nucleotides complement each other (A-T, G-C); how the regular and repeating structure of DNA is formed, and how, when one cell divides, two DNA molecules are formed.

All three [Watson, Crick, Wilkins] restarted their respective research two days after finding ‘Photo 51’, driven by the race to beat Pauling. Within ten days (February 10), they had figured out that DNA is made of two anti-parallel strands. Until February 19, they were struggling with how homo-pairing or purine-purine or pyrimidine-pyrimidine pairing might work, before meeting Donohue on February 20. It was then that Donohue corrected the atomic structures [tautomeric forms] of G and T.

It was only after Donohue’s correction that the Lego pieces fit! Only then did they arrive at the ‘base-pairing’ model we know today. They realized that purines pair with pyrimidines. Based on that, by February 28, they had solved how base pairing (A-T, G-C) occurs. Along with the solution emerged the double helix model of DNA we know today: helical, anti-parallel, two-stranded.

The Secret of Life

On the night of February 28, 1953, Watson and Crick reportedly went to a pub in Cambridge, bought beer for everyone, and announced, “We have discovered the secret of life.” Within a few days, by March 7, they had prepared the complete model of DNA.

The news spread everywhere that Watson and Crick had discovered DNA. The following month, on April 25, their paper was published in Nature, titled ‘Molecular Structure of Nucleic Acids’. The paper did acknowledge Rosalind, the author sequence was Watson, Crick, Franklin and Wilkins.

If Rosalind had lived until 1961, perhaps she too might have received the Nobel Prize, maybe instead of Wilkins. We can speculate now, but history has many Rosalinds; wasn’t something similar seen even in this year’s Nobel Prize?

As biology took another leap forward, it seemed then that all the secrets of life might now be revealed. But it turned out there was much left to discover, which unfolded later. There is another fascinating world concerning which DNA in our chromosomes becomes RNA and when-something we learned much later, and many aspects are still unknown. But science is in continuous search, aiming to delve deeper and find solutions to many things.

This article was first published in Ukalo National Daily in Nepali on April 16, 2025. I have tried to roughly translate it into English today. The Original Article can be found here: रोजालिन्ड फ्रांकलिन: डीएनएको खोजीमा भुलिएका योगदान

Leave a comment