Sargon’s Victory, Lugal-Zage-Si’s Fall, and the Shift of Mesopotamia’s Power

The Sumerian king, Lugal-Zage-Si, at one point even claimed to have conquered all the land between the “upper sea and lower sea”, meaning the Persian Gulf and the Mediterranean Sea. This was most certainly an exaggeration.

“The great god Enlil gave the kingship of the land to him. The region from the lower sea through the Tigris and Euphrates to the upper sea. Thirty-two kings gathered against him, but he defeated them and smot their cities, prostrated their lords, and destroyed the whole countryside as far as the silver mines.”

Enlil and Nupur: The city of Sumerian gods.

In the Sumerian legends, there are three main gods who dominate the pantheon. An, the sky father; Enki, the wise lord of the waters; and Enlil, the god of the “between”- air, space and breathe where, authority exist.

In the early centuries of third millennium BCE, Sumerians elevated Enlil from the local city god to the chief god of Sumerian culture. In this age of Enlil, Ruling Sumer meant more than holding cities like Uruk or Ur; it meant holding the ‘mandate of Enlil.’

During the fourth millennium BCE, Nippur was not a political power. Situated along the Euphrates, Nippur was never the richest, nor the most fortified city. It never had the influence of a conquering dynasty. However, its central geographic position- roughly midway along the Euphrates’ course- made it accessible to all major cities. Nippur’s power came from a different source: it was the home of Enlil, and by extension, the home of all Sumerian kingship.

The temple of Ekur, in the city of Nippur, became its earthly residence. This wasn’t a ceremonial notion- Sumerian inscriptions consistently depict kings who travelled to Nippur to present offerings and receive legitimacy. When Lugal-zage-si emerged from Umma and began conquering rival city-states, Kish, Larsa, Ur, Uruk- political power alone was not enough. Without Enlil’s blessing, his rule would be incomplete.

In the ebb and flow of Mesopotamian history, Uruk rose, then Ur, then Akkad, then Babylon. Each in turn marched their armies to Nippur, bowed in its temple, and declared themselves chosen. Empires came and crumbled; Nippur endured – the quiet city that crowned the mighty and buried their ambitions beneath the sands.

Lugal-zage-si and the Dream of Ruling Between the Seas.

The rebellion against the hated empire of Lagash gave rise to the rebel- Lugal-Zage-si. After sacking Lagash, Lugal-zage-si’s momentum was unstoppable. He worked his way north, up the course of the two rivers, and soon conquered all the regions that Lagash once claimed. He did not stop on the boundaries of Lagash entirely though.

At one point, he even claimed to have conquered all the land between the “upper sea and lower sea”, meaning the Persian Gulf and the Mediterranean Sea- most certainly an exaggeration. The Sumerians, up until this time, had never been able to maintain distant colonies or occupied far-off land for very long. One inscription reads:

“The great god Enlil gave the kingship of the land to him. The region from the lower sea through the Tigris and Euphrates to the upper sea. Thirty-two kings gathered against him, but he defeated them and smot their cities, prostrated their lords, and destroyed the whole countryside as far as the silver mines.”

This was the first time a Sumerian Prince has ever made this claim- king of Land between the seas. For the Sumerians, the upper sea was the western edge of their known world. The idea of a ruler who could conquer all the land between the seas lingered in the imagination of all the king that came after him.

Like king Eannatum before him, Lugal-zage-si made the critical mistake of overstretching his resources. This empire was simply too big to rule. Before long, civil wars and rebellion broke out in several Sumerian cities.

Lugal-Zage-Si and Sargon of Akkad: The first war between Sumerians and Akkadians.

In this time of chaos and instability, the other great people of Mesopotamia began to fancy their chance in ruling. These were the people, who up until this moment were the junior partner in the Mesopotamian civilization. These were the people of Akkad.

One man would soon lead them to outright rebellion against Sumerian Empire. He would go down history as Sargon, which in Akkadian means “one true king”. He would usher in the twilight of the Sumerian age.

Sargon was not of a noble birth; his story doesn’t begin with a crown. His origin story will sound familiar to anyone raised on biblical tales. Born in the 24th century BCE to a humble mother, he was said to have been placed in a reed basket and set adrift, only to be found by a gardener working at the palace of Kish.

Raised in obscurity, Sargon began his rise as a cupbearer to the king of Kish. In ancient Mesopotamia, it was a position of proximity – a cupbearer stood at the elbow of power, learning its rhythms and its weaknesses. The king would soon entrust Sargon with a mission of utmost secrecy.

At this time, the city of Kish was still under Lugal-Zage-si’s Sumerian empire. The Sumerian king was away on the distant campaign- possibly fighting in the lands of Syria. The young Sargon was given a small band of fighting men and told to travel to Uruk, where Lugal-Zage-si kept his royal capital. Their plan was to strike the city in surprise attack, to knockout the capital of this new empire and free the city of Kish from imperial control.

The tall walls of Uruk were daunting for young Sargon, but Lugal-Zage-si had taken much of his army with him in the campaign and left only a few behind to defend the capital. The attack came as a complete surprise for the already thin defensive forces.

Sargon’s men overcame their defenses and stormed over the walls of Uruk. Sargon captured the city, and before re-enforcements could arrive, he broke down several sections of the mighty walls of Uruk in a deeply symbolic act.

The Sumerian King, Lugal-Zage-si, was enraged. He marched back home gathering as many as fifty subject kings according to inscriptions. Their mission was easy enough- to crush the forces of one city state. We don’t know how he did it but in the pitched battle, Sargon’s army that emerged victorious against the whole amassed army of the empire.

Sargon captured Lugal-Zage-si and marched him through the gates of the holy city of Nippur. Sargon brought Lugal-Zage-si to humiliate In front of God Enlil, making him wear a neck stock- a heavy piece of wood clapped around his neck and shoulders.

This would have been a public humiliation, but Sargon also sets apart from other kings of the time. The old king, Lugal-Zage-si was not killed, incredibly, he was allowed to continue on as a governor of Uruk, so long as he swore an oath to the high king Sargon.

The Rise Akkad: No Longer a Junior Partner in the Seats of Power in Mesopotamia.

The victory over Lugal-zage-si did not just mark the end of one man’s reign- it marked the end of an age. With the Sumerian coalition broken and its most powerful emperor humbled, Sargon turned to the task of building something new.

Sargon did not make Uruk, Kish, or even Nippur his capital. Instead, he founded the capital city of his own- , the city of Akkad. Akkad was a statement from Sargon, a deliberate rejection of old rivalries. Akkad was a political center that listened to Sargon (of Akkad) instead of any Sumerian city- Gods like Enlil.

From there, he would go on to conquer much of what the preceding empires had before. One inscription beneath of statue in the city of Nippur claims:

“Sargon, the king of Kish, triumphed in 34 battles over the cities, up to the edge of the seas, and destroyed their walls. He bowed down to the gods, and gods gave him the upper land- up to the cedar forest and up to the silver mountains.”

Sargon also did not make the mistakes made by his predecessors. All the cities he conquered, he made a point of destroying city’s walls reducing their ability to defend or mount a rebellion. After establishing an Akkadian empire, he conducted a ceremony to symbolize his mastery over all the land. He washed his weapons in the waters of both the Persian Gulf and Mediterranean Sea.

Once the dust of war had settled, Sargon went onto strengthen and standardize his kingdom. He centralized the administration of his empire and reformed the dating system. In many ways, he was something of a progressive and enlightened leader. But Sargon was also Akkadian, and he was in today’s standard: an Akkadian nationalist.

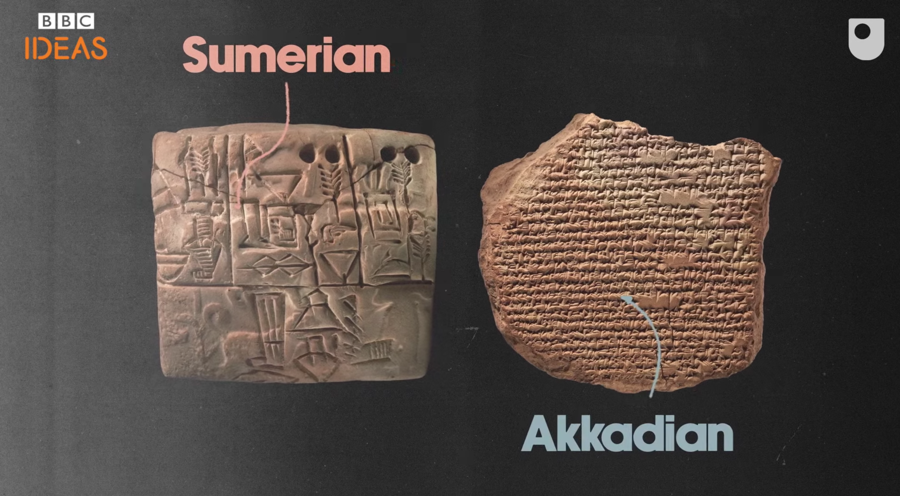

Sargon gave himself a new title, King of Akkad. He appointed only his fellow Akkadians to key positioned in his new empire. Sumerian had been the official language of royal inscriptions, on palaces and temples of Mesopotamia for hundreds of centuries. During Sargon’s reign, Akkadian began to be used in official inscriptions for the first time.

The Cuneiform alphabet was now re-engineered to write Akkadian. The language of administration shifted to Akkadian while Sumerian retained its sacred place in religion and scholarship for the time of his reign.

The two people of Mesopotamia, who had lived and grown together for thousands of years were beginning to drift apart. Resentment in the southern Sumerian speaking cities began to reach the boiling point.

Sargon ruled for fifty-five years and towards the end of his reign this resentment turned into a full-scale rebellion. One later Babylonian inscription recalls –

“In his old age, all the lands revolted against him, and they besieged him in Akkad the city. But he went forth to battle and defeated them. He knocked them over and destroyed their vast armies.”

In many ways, Sargon’s flare for battle kept his empire together but as the old king weakened virtually all the southern cities burst out in open rebellion. When Sargon died around the year 2284 BCE, his two sons had to take over and fix the mess he had left behind.

The first of his son was Rimush, he ruled for nine years spending most of them in bitter battles to reconquer the rebellious Sumerian city of the south. He crushed rebellions in Ur, Umma, Lagsh and Adab. One of the years of his reign is notoriously known in history as “the year that Adab was destroyed.” When Rimush died, Sargon’s other son Manishtushu took over. It seems he resorted to the terror tactics that was once used by the hated empire of Lagsh.

It would take Sargon’s grandson, Naram-Sin who would return the empire to Its former greatness. He quelled the rebellion in Southern Sumerian heartlands and returned the Empire of Akkad to stability.

Naram-Sin didn’t rule only by force, and made efforts to reconcile the two people of Mesopotamia. He broke from his grandfather’s title “King of Akkad” and ruled under a more diplomatic title “King of Sumer and Akkad”.

A New Cosmopolitan Age: Death of Sumerian as Spoken Language.

But, Naram-Sin did not entirely heal the division between these two intertwined people of the region.

The Sumerian people were no longer the primary cultural force in the region. For centuries, Akkadian was gradually replacing Sumerian as a spoken language. The Akkadian empire had been discouraging the use of Sumerian language in official documents, but more likely it was due to the cosmopolitan make-up of the Empire.

Sumerian was a language isolate. It had a different structure and sound to all the languages around it. But the people who lived in all the surrounding lands spoke language that was similar to Akkadian. They were linguistic cousins of Akkadian- all in the Semitic family of languages.

The languages of the surrounding lands had the same structure and Grammer, and even shared sounds and words with Akkadian. Learning Akkadian for them would have been like English speakers learning French, while Sumerian would have sounded more like an alien language- like Bengali- at the time.

Akkadian was naturally easier for these people to learn, and it naturally became the language of trade and commerce. The people in Mesopotamia had been largely bilingual for centuries. Gradually, all Sumerians would have learned to speak Akkadian, and fewer and fewer Akkadians would have needed to learn Sumerian.

Slowly the Sumerian language began to fade from history. The Sumerian language would be preserved in Temples and Ziggurats as the language of gods for another two thousand years, but its day as a spoken language were over.

However, the days of Akkadian empire were also numbered. When the great king, Naram-Sin died, his son Shar-Kali-Sharri took over. He was Sargon of Akkad’s great grandson. On year 4 of his reign, a lonely cosmic traveler appeared in the sky. The comet Hale-Bopp appeared in our night sky for the first time in 2213 BCE and remained visible for eighteen months.

In Mesopotamia, and all over the world, this was followed by extended period of time draught and reduced rain. This dry period was not brief; it would last for three hundred years and affected all around the world. It has been linked to civilizational collapses in Indus valley and the Egypt’s old kingdom.

Because of the extended periods with little or no rainfall, the days of food surplus was over, and naturally the first towns and cities began to be abandoned. After the death of king Shar-Kali-Shari in 2193 BCE, a period of chaos and bitter civil war chaos followed.

This dry period would bring nomadic people called Guti from north to Mesopotamia, who burned the city of Akkad so bitterly. The Guti would rule the region for hundred and fifty years, in what can be called the dark age in Mesopotamia.

The Sumerians would have another chance in history, after this dark age of Guti invasions, leading a brief period of renaissance in the region. But the Environment that once gave rise to this civilization would gradually claim the land back, and all of the great cities that ruled the region for ages.

Leave a comment