“Enlil what destruction he wrought. He raised his eyes to the mountain and mustered the whole mountain as one. The rebellious people, the land whose people is without number- Gutium, that land that brooks no control, whose understanding is human but whose appearance and stuttering words are that of a Dog. Enlil brought them down from the mountain in vast numbers. Like locusts, they covered the earth. Nothing escaped their arm. No one escaped their arm. All the lands raised a bitter cry on city walls.”

Hale-Bopp: The Lonely Cosmic Traveler That Brought Omen to the Sumerians.

When the great Akkadian King Naram-Sin died in 2218 BCE, his son Shar-Kali Sharri not only inherited the throne but a kingdom already in decline. In year four of his reign, a great celestial sign appeared in the skies. Nearly 200 million kilometers away, a frozen wanderer- forty kilometers wide, a ball of ancient ice and dust- passed close enough to blaze across the Mesopotamian night.

This was the comet Hale- Bopp, which appeared in our sky for the first time in 2213 BCE. It would spend the next four millennium flying through our solar system in a deep elliptical orbit until it flew past earth again as ‘blazing streak of light’ in 1997.

In that modern return, Hale-Bopp became the brightest comet in living memory. For eighteen months it remained visible in our night skies, its glowing tail stretched across the sky, dazzling millions. But awe was not its only legacy.

In March 1997, thirty-nine members of an apocalyptic cult called “Heaven’s gate” committed suicide. They all wore Nike’s “Just do it” shoes and drank a lethal mix of Vodka and Phenobarbital and slept together. They believed that their souls would be carried away in a spaceship that was hidden behind the iridescent tail of this comet.

If it could inspire such faith in the twentieth century, we can imagine what fears and omens must it have sparked in the imaginations of the Sumerians? Some may have seen a divine blessing in its light. Others, a solitary traveler whose appearance signaled catastrophe. In time, it was the latter view that would prove correct.

The 4.2 Kiloyear event: A Sudden Shit in Climate Brought Down Civilizations World-Wide.

During the reign of king Shar-Kali-Shari, the world’s climate underwent a sudden and mysterious shift. Today, scholars call this by its cryptic name, “4.2 kilo year event”. This 4.2 ka event has been tentatively linked to changes in the North Atlantic Sea ice, which rippled through the Earth’s delicate and intimately interlinked climate system. These disruptions altered air circulation patterns, dramatically reducing rainfall across vast regions of the world.

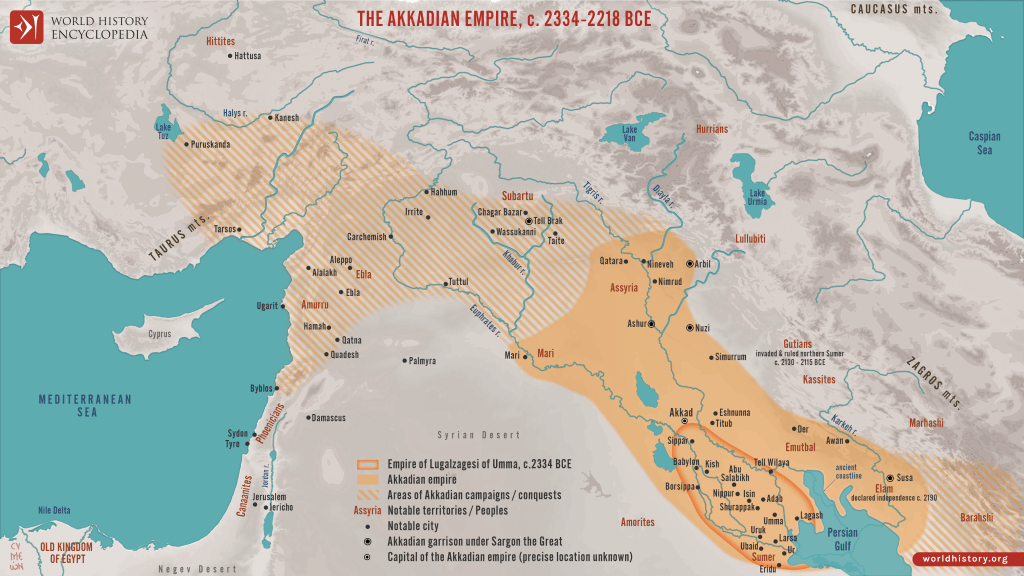

This event and the following draught are linked to civilizational collapses all around the world. Egypt’s Old Kingdom withered. The Indus Valley civilization shrank. The Liang Zhu culture in China collapsed. And in Mesopotamia, the rains withdrew, the ground hardened, and the two rivers that had fed empires no longer rose with their old generosity.

Following this 4.2 Ka event, periods of reduced rainfall and arid weather followed all over the world. This dry period was not brief either, it would last for well over a century some say even for three centuries. In Mesopotamia, Studies of dust layers show that, around this time, annual rainfall dropped dramatically, and the climate became much more arid. The annual floods of the rivers on which so much of the agriculture of the region depended would now routinely fail and famine would set in.

In Mesopotamia, still ruled by the Akkadian Empire, its resources clearly began to grow scarce. The days of booming food surpluses were over. Around this time, the first towns and cities began to be abandoned in the drier regions of the north. When King Shar-Kali-Sharri died in 2193 BCE, a period of civil war and bitter chaos set in the Empire of Akkad. The Sumerian King List records this period with a sarcastic tone:

“Then who was king, who was not the king. Four of them ruled in only three years”.

The Gutian Period: A Miniature Dark Age in Mesopotamia.

All this chaos did not go unnoticed. The people in the north- the Guti- were watching as the great Akkadian Empire started collapsing on its own.

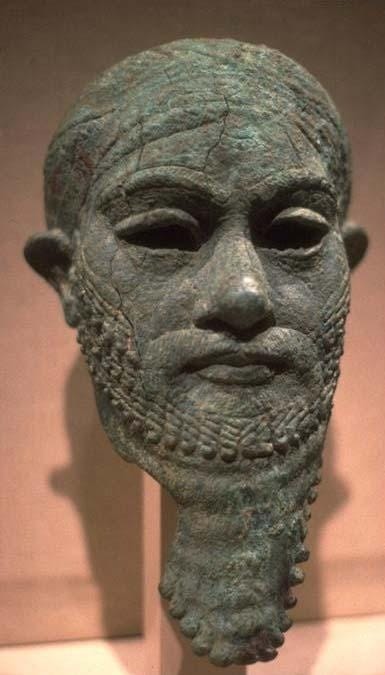

The Guti were an unsophisticated nomadic tribal people who wandered in the northern mountains overlooking the Mesopotamian plains. Who the Guti were, what language they spoke, and which gods they worshipped remain unclear. In ancient Sumerian and Akkadian texts, we find particular contempt for them:

“The Guti were unhappy people, unaware of how to revere the gods and ignorant of right religious practices.”

The Guti had raided and plundered along the borders of the Akkadian Empire for years- burning villages and stealing cattle. For years, these tribal hill people had watched as the drought ravaged the settled society of the river valley. They watched as the city dwellers fought over increasingly scarce farmland, as they themselves found it difficult to survive.

At this time of hardship, the Guti decided to gather their forces and march down from the hills into the lands of Sumer- this time not just to invade, but to take the land for themselves. The people of Sumer saw it as punishment from the god Enlil. One remarkable text from the period, The Curse of Akkad, provides an incredible description of the events of this Guti attack:

“Enlil what destruction he wrought. He raised his eyes to the mountain and mustered the whole mountain as one. The rebellious people, the land whose people is without number- Gutium, that land that brooks no control, whose understanding is human but whose appearance and stuttering words are that of a Dog. Enlil brought them down from the mountain in vast numbers. Like locusts, they covered the earth. Nothing escaped their arm. No one escaped their arm. All the lands raised a bitter cry on city walls.”

The Guti army quickly overwhelmed the weakened Akkadian forces. Before the full-blown invasion, they practiced hit-and-run tactics- raiding supply lines and leaving burned cities behind them. Their attacks devastated the economy of Akkad, and the already downtrodden society began to fall apart. The famished and weakened Akkadian society folded completely under Guti attack. The demoralized Akkadian army went on to meet the amassed Guti in battle, and they stood no chance. The Guti swept Akkad and destroyed Sargon’s city so thoroughly that we have never been able to locate its ruins.

For the following hundred and fifty years, the Guti ruled Mesopotamia in misery; it can be called a dark age. There is little written record or art from this time, and the ones found are unsophisticated. The Guti showed little concern for maintaining agriculture, written records, or public safety.

For reasons unknown, they also did not believe in keeping animals in pens and released farm animals into the wild. The Guti were not literate and would have struggled to administer an empire which for over a millennium had relied on the written word. Their policies soon brought even further famine, and under neglect the existing infrastructure started to crumble.

Third Dynasty of Ur: Utu-Hengal and a Neo-Sumerian Age.

As resentment to the Gutian rule grew, eventually rebellions stirred in Southern Iraq. The destruction of the central authority of the Akkadian Empire meant that a number of Sumerian cities reasserted their independence. One Sumerian would soon lead a renaissance of the Sumerian age in the region, rejecting both the Guti and Akkad, at once.

We do not know much about who Utu-Hengal was, but it is clear that he was a Sumerian governor of Uruk who had witnessed and heard about his beloved homeland turned into ruins- first by the Akkadians and then driven to famine by Gutian rule. He amassed armies from other Sumerian rebel cities and declared war on the Guti once their last king, Tirigan, came to power. Tirigan had only been in power for forty days when Utu-Hengal made his move.

Before he went on to all-out war against the Gutian king, Utu-Hengal bowed down to the Sumerian Gods. He traveled to the temple of Ishkur, the Sumerian god of storm. He offered an ancient prayer in the Sumerian tongue and sacrificed a lamb before the altar of the Sumerian god. The Sumerian King List writes:

“Then Tirigan, the king of the Guti, ran away alone on foot. He thought himself safe in Dabrum, where he fled to save his life. But since the people of Dabrum knew that Utu-Hengal was a king endowed by power of Enlil the people of Dabrum did not let him go.”

“Utu-Hengal made the guti, the fanged snakes of the mountains go back to drink again from the rocky crevices of the mountains. He brought the kingship back to Sumer.”

Ur-Nammu: The Sumerian Renascence and of Age of the Ziggaruts.

After centuries, Sumerians finally rejected both the Guti and Akkad. For the first time since the time of Sargon, the power of Mesopotamia was back in the hands of a Sumerian king again.

Utu-Hengal’s successful rebellion ushered in an era known today as the Third Dynasty of Ur. It is often referred to as the Neo-Sumerian Empire or the Sumerian Renaissance. It was the final flourishing of Sumerian culture- one already more than three thousand five hundred years old. This final flourishing would leave an indelible mark for all the human history to follow.

Despite bringing the kingship back to Sumer, Utu-Hengal did not rule for long. He was probably killed by one of his more ambitious governors, Ur-Nammu, under mysterious circumstances. Despite his mysterious rise to the throne, Ur-Nammu went on to become an outstanding leader. He was also a brilliant administrator administered a number of changes. He standardized weights and measures used in the market. He divided silver into a unit called the mina, which was made up of sixty shekels, which went on to become the foundations of the first currencies centuries later. He also wrote down a set of laws that today are the earliest surviving example of a legal code, three centuries before the more famous code of laws by Hammurabi.

Among all his other achievements, Ur-Nammu was also a prodigious builder. He rebuilt the cities of Nippur, Ur, Larsa, Kish, Adab, and Umma. He reformed the kingdom’s roads and irrigation after more than a century of neglect under Gutian rule. But more than anything, he loved to build ziggurats. Under Ur-Nammu, soon every Sumerian city would have a ziggurat, and they formed the focal points of each city in their day. Each night it would have shone in bright white under the moonlight, as it was intended- a shrine to the moon god Sin.

The ziggurats are the distinctive stepped towers that were the hallmark and pinnacle of Sumerian architecture. Each one would have risen in three layers like a wedding cake, with steps leading up to the top. They were made purely from baked clay bricks held together by bitumen. They were painted with white gypsum and would have shone brightly in the day. Priests would have planted trees and flowers on each of their steps, lighting the top floor with candles at night.

The biggest of these ziggurats was in Ur-Nammu’s home city of Ur. In its day it would have risen up to thirty meters from the surface- the equivalent of a ten-story building. It is in its ruin that the Italian traveler Pietro Della Valle found shelter in 1617 CE.

Water and Soil: How the Water and Farmland That Once Gave Life Choked the Life of Sumer.

Despite this late flourishing, the nature that once gave rise to this great Sumerian civilization would soon go on to swallow their great cities and civilization.

The water flowing from the Euphrates and Tigris rivers brought down silty soil with traces of salt and minerals. These rivers, flowing over the limestone-rich Taurus Mountains, contain more salt and minerals than most rivers. When ancient farmers used this water to cultivate their farmland in Sumer, the hot sun would evaporate the water, and traces of salt would be left behind. During times of adequate rainfall, the yearly rain and floodwater would have washed this salt away.

As the arid period lasted centuries, the soil beneath their feet started to give up. After around 2200 BCE, the arid conditions of southern Iraq meant more and more salt remained in the soil. Over time, this trace amount of salt began to accumulate, and plants started to find it difficult to grow. The Sumerians kept details of their annual crop yields, and their records after 2300 BCE show a particularly bleak picture.

One tell-tale sign of increased soil salinity can be correlated to their switch from wheat to salt-resistant barley as their main crop. In the city of Girsu, for example, around the year 3550 BCE, wheat and barley were produced in equal amounts. After a thousand years of irrigation, wheat accounted for only about six percent of the annual harvest. This was further reduced to about two percent by 2000 BCE, pointing to a sharp increase in the soil’s salt content.

By this time, the Sumerians had switched to barley as a staple in their farm as well as their diet, quite ingeniously. The Sumerians can be portrayed as damaging the soil out of greed; however, they did employ some methods to tackle the problem. They did not have our modern understanding of agriculture; they took steps such as crop rotation, resting their farmland, and draining their soils.

While the last Sumerians worked to mitigate the decline, the overall trend was slow but unstoppable. As the centuries wore on and droughts continued, the soil was gradually failing. With the population of Sumerian cities growing and droughts dragging on, the demands on these farmlands were ever growing. Eventually, a thick layer of salt encrusted the topsoil, and little would grow at all.

The same soil that once gave life to the people of Sumer slowly began to choke the life of the Sumerian people and their great civilization. But the death of Sumerian culture would come not by nature but at the tip of the spear. Ur-Nammu was killed by the Guti, and four kings followed him who continued his reforms.

However, this dragging drought would soon bring another group of nomadic people from the north, the Martu, which would begin the final death spiral of this great civilization. The Sumerian king was named Ibbi-Sin, who took the throne in 2028 BCE. As soon as he was crowned, the empire began to crumble. The death knell of the Sumerian civilization would come from the people of Elam, the people from the south in Iran, who were only beginning to flex their muscles into history at this time.

Leave a comment