Sumer’s cities, once blazing with temples and the first lines of writing, faded under the weight of drought, invasion, and time. In their ruins linger the echoes of a people who gave us civilization’s dawn, only to vanish into its earliest dusk.

The ancient Sumerians who saw the destructions of their cities reacted to their sorrow by writing poetry, as humans have always done. For each of their great ruined cities, they wrote a lament. One of such laments, “The lament for Ur”, relates with tangible anguish the horror:

“The gods have abandoned us. Like migrating birds, they have gone. Ur is destroyed. Bitter is its lament. The country’s blood now fills its holes like hot bronze in a mold. Bodies dissolve like fat in the sun. Our temple is destroyed. Smoke lies on our city like a shroud. Blood flows as the river does, the lamenting of men and women. Sadness abounds. Ur is no more”

The fall of Ur was one of the great turning points in ancient history. Ur was sacked and burned by the Elamites sometime around 2000 BCE. In the next few decades, individual city-states vied to take control over the ruins of the former empire. The wars of this time turned Sumerian cities into blackened ruins of burnt clay. The lament for Ur further adds:

“The people mourn. Its people like potsherds littering the approaches. The walls were gaping. The high gates, the roads, were piled with dead. In all the street and roadways, bodies lay. In open fields, that used to fill with dancers, the people lay in heaps.”

This marked the final death of a Sumerian society. The first human civilization, one people of Sumer and Akkadian had created over an incredible three thousand five hundred years, was no longer in existence.

Utu Hengal and Ur-Nammu: The Twilight of Sumerian Society.

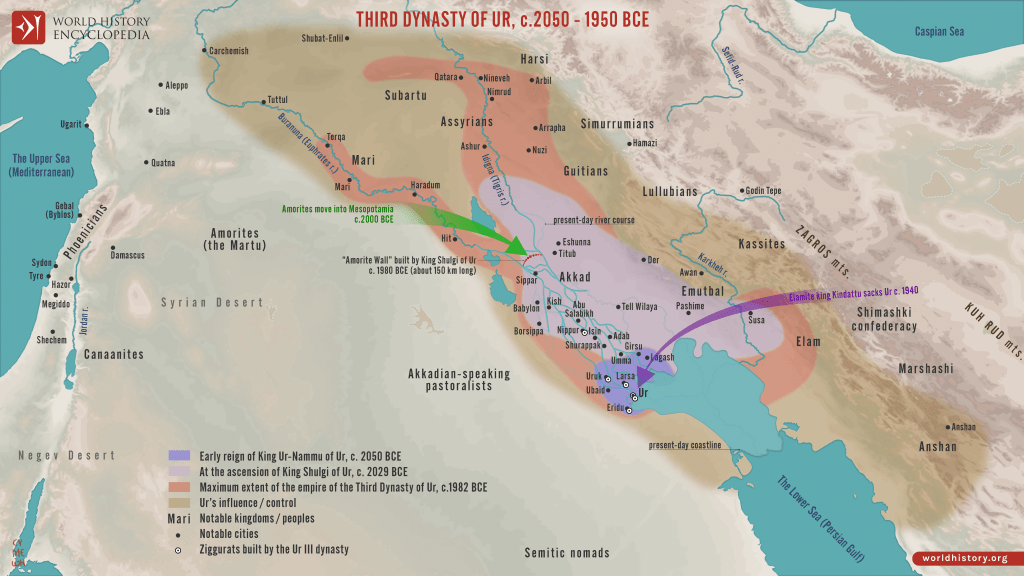

Utu-Hengal defeated the last Gutian King, Tirigan and brought the power back to the people of Sumer. He went on to establish a Neo-Sumerian empire, referred to as the ‘Third dynasty of Ur’ or simply “Sumerian Renaissance.” Utu-Hengal’s successor, Ur-Nammu, despite his mysterious rise to power, turned on to become a brilliant administrator and builder, who constructed Ziggurats and oversaw reforms that defined this renaissance.

The Guti had now retreated to the mountains and returned to their nomadic ways. However, they still posed significant threat to the Sumerian towns- raiding cities and stealing cattle- as they always had. Putting a stop to these raids was the focus of much of King Ur-Nammu’s reign. He raised an army and marched into Gutium with the aim of stopping this Guti threat forever. However, He was killed by one of the typical Guti ambushes in the mountains.

The death of this last great king would begin a final death spiral of the Sumerian culture. The death of this beloved king is commemorated in a lengthy epic called “The Death of Ur-Nammu”:

“He who was beloved by the troops could not raise his neck anymore. The wise one lay down. Silence descended, as he, who was the vigor of the land, had fallen. The land becomes demolished like a mountain. Like a Cyprus forest, it was stripped, its appearance changed.”

The poem tells the story of Ur-Nammu descending into the underworld and giving his offering to the Gods who lived there. And in the afterlife, the epic gives Ur-Nammu his final lament:

“Now just as the rain pouring down from heaven cannot turn back. I can never return to see the beautiful bricks of Ur”.

Draught, Famine, and the Martu: The Last Days of Sumerian Empire.

Ur-Nammu was killed by the Gutian ambush in 2094 BCE; four Sumerian kings would follow him. Ur-Nammu’s successor, King Shulgi, enjoyed successes in the battlefield and reformed the economy as much as they could. However, the reigns of kings who followed him were all marked by ongoing threats from the wild mountain regions.

The draught was still biting, and the soil was becoming increasingly choked by accumulating salt layers. As food got scarce, more and more nomadic people were driven to raiding and plundering to feed themselves. By now, the Guti were the only nomadic tribe who threated the borders of Sumer.

One tribe in particular, known as Martu, posed the biggest threat. The Martu were sematic speaking, sheep herding, people from the mountains of Syria and Lebanon. Similar to the Guti, the Sumerians considered Martu to wild and barbarous and described them often in contemptuous and fearful terms:

“The hostile Martu have entered the plains. The Martu, a ravaging people with canine instinct, like wolves.”

“The Martu, the powerful south wind, who from the remote past have not known cities. The Martu, who know, no grain. The Martu, who know no house or town. The savages of mountains, the Martu who eats raw meat, who are not buried after their death”

It is clear that by now the Martu were finding their nomadic way of life in the mountains of Syria increasingly impossible. The ongoing draught and famine were pushing them south- into the rich farmland of the river valley- to the land of the Sumerians. Despite the weakened power of the Sumerian state, they were determined to stop the Martu incursions. The new Sumerian king Shu Sin, who followed Shulgi, even ordered the construction of a giant wall between Tigris and Euphrates River.

The construction of this wall would have been an enormous engineering work and shows that even in its final years, the Sumerian state still commanded considerable manpower and energy. This wall, known as the Martu wall, was around three hundred kilometer long, more than twice the length of Hadrian Wall in Britain. Archeologists have never been able to find this wall, and one can only guess what form it took. This Martu wall would have turned the rich farmland between Tigris and Euphrates into an island fortress- river on either side, sea to the south and wall to the north.

However, like all walls, the Martu wall was only effective with the constant garrison manning it, and as it was no longer possible in weakened Sumerian state, it would fall soon. Ultimately, the building of this wall was not an act of strength but a last resort of an empire falling in on itself. Walls work as long as the invaders don’t make bigger ladders.

Elam Sacks and Burns Ur: The Final Collapse of Sumerian Civilization.

The last Sumerian King was a Man called Ibbi-Sin; he took the throne in 2028 BCE. As soon as he was crowned, the Empire began to fall apart. In his first year, the eastern city of Eshunna broke free from the Empire.

An even bigger rebellion came in year three of his reign, when the city of Susa, in the region of Elam, successfully rebelled. These Elamites, People of Iranian lowland, were under Sumerian rule and at this stage just beginning to flex their muscle at the time. Their rise would soon bring the death knell of the Sumerian Age.

The fracturing Sumerian empire could no longer maintain its defenses along the Martu wall. In the fifth year of his reign, the wall- built by Ibbi-Sin’s father- failed. The Martu poured over the defenses and overran the rich farmlands that lay behind. The effects were immediate and devastating. Food shortages ran rampant. By years seven and eight, the price of food increased as much as sixty-fold. The famine hit the capital city especially hard, and people starved in the streets.

The twin pressure of invasions and ongoing famine drove Ibi-sin into panic. One remarkable letter written by his general Ishbi-Erra survives today. Ishbi-Erra had been sent to buy food from the city of Ishin, and in his letter to Ibbi-Sin, he paints a vivid picture of the collapse of Sumerian society at this time.

“You ordered me to travel to Isin and Kazallu to purchase grain. With grain reaching the exchange rate of one shackle of silver per gur, 20 talents of silver have been invested in the purchase. But I have heard news that the hostile Martu have entered inside your territories. I entered with the entire amount of grain, and now I have let the Martu, all of them, penetrate inside the land. Because of the Martu, I am unable to hand over this grain for threshing. They are stronger than me. While I am condemned to sitting around.”

The Akkadian general, Ishbi-Erra, had no intention of returning to the capital city of Ur. Soon he abandoned King Ibbi-Sin altogether, declaring himself king of Isin and Nippur. Facing threats on multiple sides, Ibbi-Sin entered into a frantic series of last-ditch measures. He fortified the important cities of Ur and Nippur, but these efforts were in vain. Ultimately, the Sumerian Empire fell apart one city at a time, until only the capital of Ur remained, surrounded by hostile forces.

Soon the people of Elam, former subjects of the Sumerians in the foothills of Iran, marched down along the hill paths, gathering with them an army of tribesmen, and laid siege to the great city of Ur. Ibbi-Sin tried one last desperate attempt to beat them back, enlisting the help of the traitor Ishbi-Erra as well as the hostile Martu, but it was all useless. The Elamites broke through the walls of Ur and set the city on fire. They poured into the sacred precincts and ziggurat, killing priests and plundering treasures as they went.

The surrounding fields were burned, and the waterways became contaminated with disease. The armies of Elam stormed the royal palace and captured Ibbi-Sin. They took him away in chains, marched him back to their homeland, and imprisoned him there. This was the last king of Sumer, a civilization that had endured for more than three thousand years. Ibbi-Sin would die in chains, imprisoned by his enemies in a foreign land.

The Fall of Ur: A New post-Sumerian World Order and Gradual Collapse of the Great City.

The fall of Ur is one of the defining turning points in history. It marked the end of a unified Sumerian state, and the region entered a dark age, in which individual city-states vied to control the ruins of the former empire. Meanwhile, the drought dragged on. The salt-ridden fields were no longer producing barley. Faced with these problems, the Sumerian people began to flee the region in huge numbers, carrying with them their meager belongings and lamentations for their great fallen cities.

Over the next centuries, a vast population movement took place- from the south of Mesopotamia to the north. Many Sumerian speakers settled in Akkadian lands. They were even joined by the Martu, who had settled down in the cities they had conquered. The fleeing Sumerians, the migrating Martu, and the native Akkadians mixed together. They blended their cultures, as the people of this region always had. The foundations they laid would give rise to the next chapter of Mesopotamian history and form the region’s new superpowers- the Babylonian and Assyrian empires.

Sumerian was now a dead language. It would never again be heard in the streets and markets. Gradually, it was lost from the memory of the people. Yet it survived in their temples, much as medieval churches preserved Latin after the fall of the Roman Empire. Later rulers preserved the Sumerian language in their temples and scriptures for at least another two thousand years. For these later people, Sumerian became a language of the gods, and the kings of Ur and Uruk turned into legends, some even revered as gods themselves.

All the kings of Mesopotamia, in Babylon and Assyria, for the next two thousand years, would rule under a title that gave them ancient legitimacy. King of Sumer and Akkad– reaching back to the first age, the dawn of mankind’s journey into civilization.

The Death of Ur: The ruins where Italian Traveler Pietra Della Valle Found His Shelter.

Even after the fall of the Sumerian Empire, Ur continued as a population center. It would rise and fall a number of times over the next centuries of the post-Sumerian era.

Ultimately, it was the landscape that had given birth to Ur, and it was the landscape that would bring its death. Today, the Persian Gulf that once gave rise to Ur lies nowhere near its ruins. Archaeologists were astonished to find remains of millions of seashells scattered in its ruins when Ur was discovered in 1815 CE, deep in the desert. Over the millennia, the continual depositing of silt, along with changing global sea levels, pushed Iraq’s gulf coast back to its present position- about one hundred kilometers south of Ur.

The Euphrates River that once brought rich bounties of trade down from the north has also disappeared, its course having shifted over the centuries. Today, there is nothing but miles of desert around its ruins. Water had always been the city’s lifeblood. The loss of the sea and river meant the slow death of Ur.

People soon left its houses and streets. They stopped working their fields and maintaining irrigation canals, and the land dried up, the topsoil blowing away in the wind. The priests extinguished the fire that burned on the top chamber of the ziggurat and stopped leaving their offerings to the moon god, Sin. The markets closed, the mudbrick buildings crumbled, and the wooden beams rotted and fell in.

The desert wind and sand rolled through its streets, and the dunes buried its fallen walls. Before long, the greatest city the world had ever known was just a mound of ruins, where the occasional desert traveler might pass by. It was in these ruins that the Italian traveler Pietro Della Valle once took shelter with his wife, hiding from bandits. Through him, we discovered the scattered fragments of writings that the Sumerians left behind in their forgotten language. Somewhere buried in the ruins of Ur lie the clay tablets where the Lament for Ur was written:

“May that storm swoop down no more on your city. May the door be closed on it like the great city gate at nighttime. Until distant days, other days, Future days. In your city reduced to ruin mounds may a lament be made to you. Oh Onana, may your restored city be resplendent before you.”

The Fall of the Sumerian Cities: Desert, Sand-Mounds and the Letters that Survived.

Following the sacking of Ur around 2000 BCE, the city of Uruk went into steep decline and much of its population fled. Uruk did experience another period of revival when it served as a regional capital in the later Assyrian Empire. But as the Euphrates River changed its course, Uruk too was completely abandoned.

Today, the walls of Uruk- the same walls described so vividly in The Epic of Gilgamesh– are still visible. Heaps of ancient brickwork line the flat lunar landscape of the desert. They still rise fifteen meters high, encircling a city now washed by a tide of broken pottery and bones. English archaeologist William Loftus was the first European to reach Uruk. When he discovered its ruins in 1849 CE, he was struck by the haunting sight of vast mounds rising out of the desert. He later wrote of these mounds: “Of all the desolate sights I ever beheld, that of Uruk incomparably surpasses all.”

The process of decay in all the ancient cities of Sumer- in Nippur, in Eridu, in Kish and Lagash, and in Ur and Uruk- would have been gradual but unstoppable. Windborne sand piled up against the walls that still stood and filled the streets. Rainwater and wind wore down the remaining structures. The occasional travelers who encountered these lonely ruins must have told stories about what happened to the people who built such enormous structures and disappeared altogether.

With their cities in ruins, the Sumerian people passed out of history. The civilizations that replaced them- who kept their language alive in their temples and told stories of their kings- would themselves pass into ruin. The knowledge of how to read Sumerian was forgotten, and its history turned to dust. Only their clay tablets remained, buried in the sands of Iraq’s desert- fragments containing the voices of a whole people, waiting for archaeologists to find them and, through arduous and painstaking work, rediscover how to read them.

These fragments give us little bursts of light from this most distant past. They tell us about the records and recipes of the Sumerian people, their music and their prayers, their loves and their grief, their triumphs and their beautiful sorrowful lamentations for the loss of the first cities. The tablets give us the wistful philosophies of these most ancient people, as lines from The Epic of Gilgamesh show:

“Nobody sees death. Nobody sees the face of death. Nobody hears the voice of death. Savage death just cuts mankind down. Sometimes we build a house, sometimes we make a nest, but then brothers divide it upon inheritance. Sometimes, there is hostility in the land, but the river rises and brings floodwater. Dragonflies drift on the river, their faces look upon the face of the sun but then suddenly there is nothing.”

Wooly Mammoths outlived the Sumerians.

Before I end this series, I want to go back to the Wooly Mammoths. When the Sumerians reached Iraq’s southern coast for the first time around 5500 BCE, the last of the Wooly Mammoths were fighting for their survival on the other side of the world.

They had made Wrangel Island their home and fought to endure, just as the Sumerians were sowing the seeds of the first civilization in human history in Southern Iraq. On that small rocky island on the edge of the Arctic Ocean, the last of the woolly mammoths lay down and died. This was sometime in 1700 BCE, when the last kings of Ur were already a distant memory.

Sumerian society, in its imperial form, had risen, lived out its golden age for more than three thousand years, and died- outlived by the Woolly Mammoth.

Leave a comment