From the collapsed dynasties of ancient Egypt to the hemophilia of Victorian Europe, the human quest for “lineage purity” has come at a devastating biological cost. This article explores how endogamy and consanguineous marriage have acted as a “genetic prison,” narrowing our diversity and exposing us to hereditary diseases- and why breaking these ancient walls is vital for our species’ future.

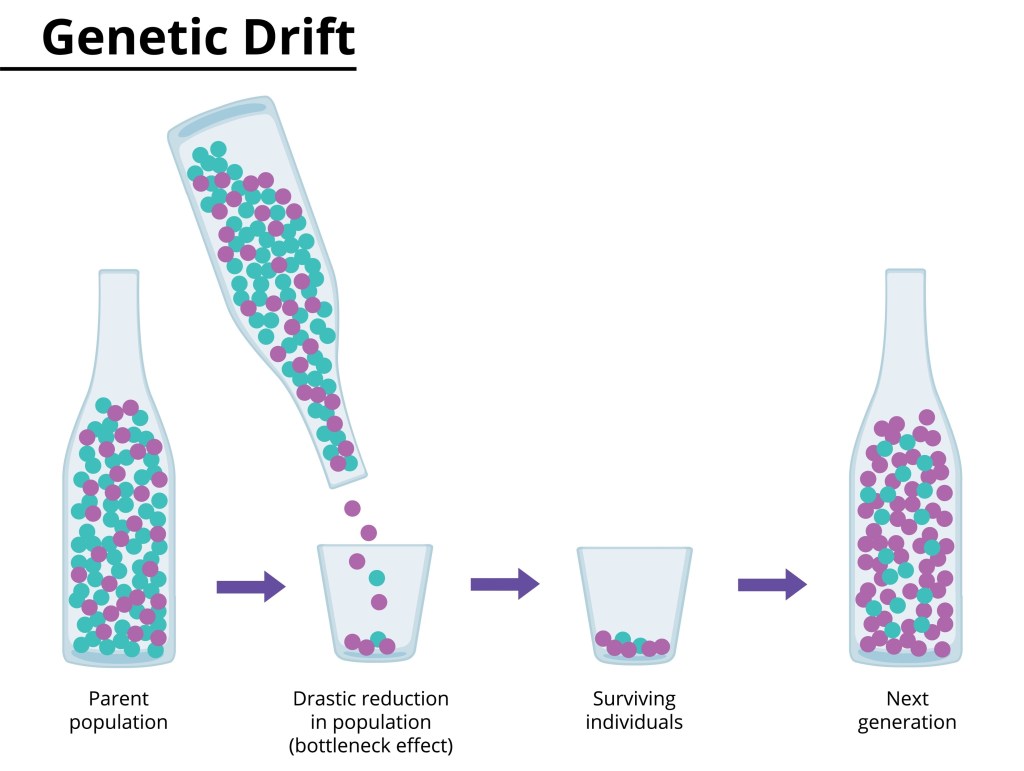

We, the human species, have arrived at this point in time after facing numerous forms of destruction throughout our evolutionary history. Having split from the common ancestors of primates (monkeys) nearly 500,000 years ago, we are relatively new compared to many other species in nature. Our species, Homo sapiens, came into existence only about 300,000 years ago, evolving into modern humans after surviving the genetic bottlenecks caused by the Toba super volcano and climate change, the harshness of the Ice Age, and numerous geographical obstacles.

Endogamy: How marrying within the community and family shrank genetic diversity

We survived external hardships to get here, but by erecting various walls within ourselves, we have contributed to the further constriction of our genetic diversity. This practice- continuing continuously under various guises to preserve the “purity” of one’s lineage and community since the dawn of civilization- has increased the risk of various genetic diseases.

Living as hunter-gatherers for much of the primeval age, we evolved without these boundaries for a long time. Civilization only truly began after a hunter-gatherer woman living in Turkey around the Taurus Mountains learned to farm for the first time nearly 15,000 years ago. With the expansion of civilization, the desire to seek “connection”- with a clan (Kula), religion, caste, community, or dynasty- became our nature.

We began to marry within our own clan, our own caste, and our own community and religion. These boundaries, created alongside social development, narrowed the genetic diversity that nature’s irregularity naturally increases. The tradition started to preserve the identity and purity of a community or lineage has, over time, turned into a “genetic prison.” This is the paradox of our evolution: the more we spread geographically, the more we have constricted the diversity of our genes- our genetic diversity- by imposing various geographical, social, and cultural structures.

The obsession with “Pure Lineage”

As the custom of kingship began in early civilizations, the tradition of marrying within one’s own family started to preserve the purity of the dynasty. This practice of marrying within the immediate family or close relatives, started by kings and later followed by subjects, further shrank our already limited genetic diversity, resulting in the emergence of many genetic diseases.

The Pharaohs of Ancient Egypt: The Tomb and Evidence of Tutankhamun

Anyone interested in ancient Egypt has likely heard the name “Tutankhamun.” Tutankhamun was the King, or Pharaoh, of Egypt for only a short time. After his death, the tomb containing his body remained closed in the desert for nearly 4,000 years. His name became famous because his tomb, found by archaeologists in the early 20th century (1922), was the first Pharaoh’s tomb untouched by looters. A remarkable natural coincidence lies behind why his name is heard more than any other Egyptian King/Pharaoh.

Scholars of ancient Egypt divide its nearly 3,000-year-old civilization into three main periods: the Old, Middle, and New Kingdoms. When we think of Egypt, we think of pyramids. However, Pharaohs were only placed in pyramids after death, only for a few centuries during the Old Kingdom. By the time of the Middle Kingdom, they were fed up with pyramid looters. It was then that the custom began of burying dead kings in the “Valley of the Kings,” far from the pyramids of Giza. Tutankhamun, who died at the age of thirteen, was a Pharaoh of the final era of ancient Egypt, the New Kingdom.

Most Pharaohs’ tombs could not escape the looters who came later. When geologists found and opened Pharaohs’ tombs, the mummies and offerings placed inside had usually already been stolen. Tutankhamun’s body was also placed in the Valley of the Kings. A few years after Tutankhamun’s death, a massive flood occurred in the Nile, submerging the Valley of the Kings for the first time. Because of that flood, Tutankhamun’s tomb remained hidden and preserved for 4,000 years until it was opened in the early 20th century.

Inside the tomb, it wasn’t just his mummified body; there were many other offerings, all wonderfully preserved. The study of Tutankhamun’s body and other materials found in the tomb provided concrete evidence for the first time that the royal family of Egypt’s New Kingdom practiced inbreeding- marrying within their own family- to preserve the purity of the “Divine Lineage.”

Tests on Tutankhamun’s body revealed that his parents were biological brother and sister. Tutankhamun, who died young, had a congenital clubfoot, abnormal bones, and other bodily weaknesses. Tutankhamun is proof that the rulers of Egypt’s New Kingdom had a long-standing practice of inbreeding. This hereditary custom, intended to preserve the ‘divine purity’ of the dynasty, resulted in various physical deformities in other Pharaohs as well. Tutankhamun died young as a result of genetic disorders caused by long-term inbreeding. In his tomb, the mummies of his sister-wife and two stillborn daughters were also found. All three of them shared congenital deformities similar to Tutankhamun’s.

The spread of the “Divine Lineage” tradition to later courts

Nearly 4,000 years ago, Egyptian Pharaohs had no knowledge of genetics, and modern social values were out of the question. Due to the continuous practice of inbreeding to save the royal family’s divine purity (believing that marrying outside the family would taint it), many other Pharaohs of the New Kingdom, like Tutankhamun, died young due to similar genetic diseases. Genetic diseases played a significant role in the fall of ancient Egypt. The Greek (Ptolemaic) rulers who came to govern Egypt after Alexander conquered it were also found to have continued this tradition of the Pharaohs. A famous queen of the Ptolemaic dynasty was Cleopatra. The Roman Emperor Julius Caesar made both Egypt and Cleopatra his own. Before marrying Cleopatra, Caesar had defeated her own brother-husband in war.

For many royal families, the purity of the lineage was more important than anything else. This custom of the Egyptian royalty also ran through Greek and Roman civilizations. Much later, such practices were frequently seen in European royal families as well.

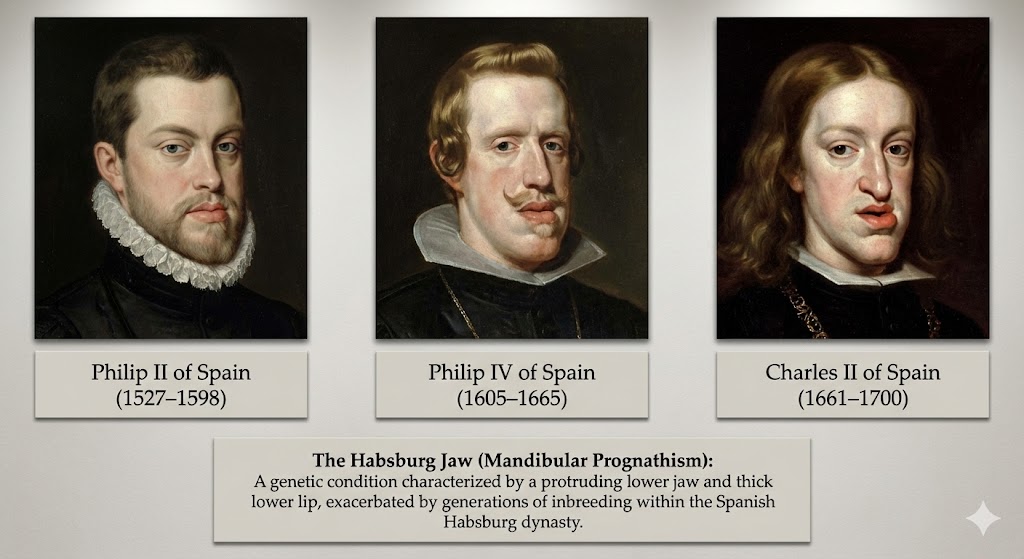

At one time, the Habsburg family ruling Spain married only within their own family for a long time to preserve royal purity. The effect of interbreeding was visible in all descendants as the “Habsburg Jaw.” Charles II, who died of genetic diseases caused by inbreeding, took his dynasty down with him.

Not only in Europe, but the Japanese Imperial family also had a custom of marrying only within four specific families of the capital. It was only after World War II that they realized this experiment, which lasted nearly 800 years, had resulted in the average height of Imperial family members being lower than that of other Japanese people. Since then, members of the royal family have been encouraged to marry outside those families as much as possible.

This trend, started to save the purity of the royal lineage, was not limited to royal courts. The community beliefs we see today- that one should only marry within the same religion, caste, or community, or only if the Gotra, Varna, and stars match- are remnants of this. Endogamy, or the practice of marrying only within the same caste, religion, or community, deepened in society alongside the development of civilization. This tradition, started to protect social identity and family purity, has played the most significant role in the decline of our ability to fight diseases.

Why is there a risk of genetic disease when marrying close relatives?

The mystery of these hereditary genetic diseases lies in our DNA. We all have roughly the same twenty-three pairs of chromosomes. Inside the chromosomes, made of DNA containing nearly 3.5 billion nucleotides, there are about 30,000 genes that make proteins. Which gene works when, and the proteins they subsequently create, determine all types of cells in the body, organ types, and various bodily processes. Not all genes are working all the time; on average, only about 10,000 genes work at once in any cell of the body.

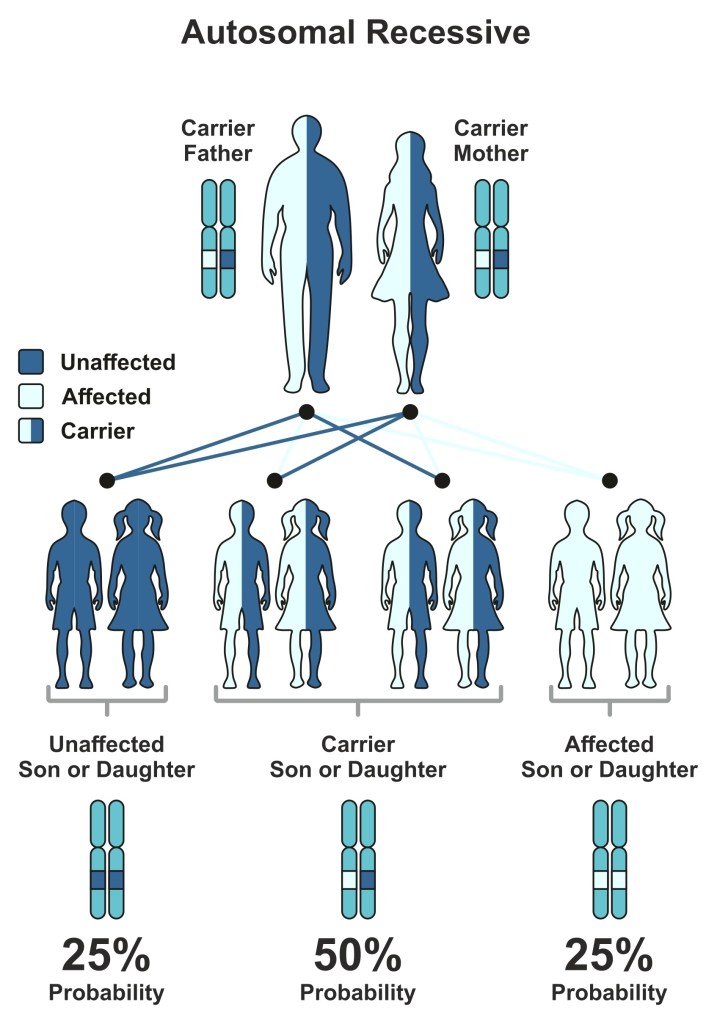

There are two copies of alleles within a gene- one copy comes from the mother and the other from the father. Which of these alleles gets to work, and when, plays an important role in the gene’s function. Both alleles rarely work at once, nor can both alleles work with equal capacity. This quality of alleles is what distinguishes them into two types: Dominant and Recessive alleles. Dominant alleles usually suppress the recessive alleles of a gene that could harm the body.

Most genetic/hereditary diseases, like Tutankhamun’s broken body or the Habsburg jaw, appeared when these recessive alleles became active. The hereditary propagation of alleles determines when these recessive alleles, which are harmful to the body, will work.

In children born from the marriage of two unrelated families, the possibility of such recessive diseases occurring is low. The practice of consanguineous marriage (marrying between cousins, children of paternal uncles or maternal uncles) still exists in many Muslim-majority countries and some communities in our own country. Marriage among close relatives or continuous intermarriage within limited circles increases the possibility of other diseases caused by the appearance of recessive alleles. If a marriage occurs between the children of a maternal uncle/paternal aunt or paternal uncle/maternal aunt, the probability of recessive genes appearing in the children born to them increases by about 20 percent.

Hemophilia in European Royal Courts

An example of a disease appearing due to close-kin marriage is the ‘Royal Disease’ or ‘Hemophilia’. First appearing in Queen Victoria of Britain, this disease spread to royal families across Europe after her. Hemophilia is caused by a mistake/mutation in the genes on the X chromosome that make the protein needed to clot blood. The effect of this ‘recessive mutation’, appearing on only one allele of the X-chromosome, is not seen in women who have two X chromosomes. Queen Victoria carried this allele, but its effect was not seen in her.

The dominant allele without the mutation in Queen Victoria suppressed the recessive allele carrying the Hemophilia mutation. This recessive mutation carried by Victoria was passed down to her descendants; her sons had a 50% chance of having Hemophilia, and her daughters had a 50% chance of carrying the disease like Victoria. Victoria’s son Leopold died young due to Hemophilia. Her daughters married European princes, spreading this royal disease to many European courts. Many other genetic diseases like Cystic Fibrosis and Thalassemia are transmitted in the same way.

High rates of Diabetes and other diseases in communities with Consanguineous Marriage

In children born from marriages between first cousins (children of siblings), ineffective recessive alleles and the harmful mutations they carry appear in this very way, the effects of which cause most hereditary/genetic diseases. The transmission of X-Y chromosomes is slightly different from others, but simply put, for these diseases caused by recessive alleles to appear, both parents must have those disease-causing alleles. If one marries a close relative, the probability that both carry those alleles increases significantly. In consanguineous marriages, the probability of genetic diseases increases by 1.7 to 2.8 times.

This practice still exists in many Islamic countries, and high rates of diabetes are seen in many such countries. There are two types of diabetes, and the causes for both are different. Type-2 diabetes is caused by defects in genes that make insulin. This traditional practice of consanguineous marriage increases the possibility that defects in the genes needed to make insulin will be repeated in both alleles. In communities that practice consanguineous marriage, these multiple recessive alleles carrying mutations appear repeatedly, and the resulting defects disrupt insulin resistance and glucose metabolism, increasing the likelihood of Type-2 diabetes.

Lessons learned from History

From the beginning of our evolution, we have run various practices of marriage and reproduction continuously for generations. This practice, conducted under various guises to save the purity of different communities or lineages, caused our species’ ability to fight many diseases to gradually disappear along with evolutionary development. The continuously running practice of endogamy reduced the effective population of the community, narrowed our gene pool, and such harmful hereditary mutations have been collected and passed down. The danger increased by this practice of breeding within close communities is further exacerbated by the custom of marriage between close relatives.

However, some communities have made various social rules to discourage marriage among close relatives. In Nepal, the Hindu religious rule that one should not marry within the same Gotra is an example of this. Having the same Gotra means sharing a common ancestor, even if separated by different surnames.

While Gods may be tricked by them, DNA does not recognize Mantra.

The high rate of Type-2 diabetes seen in Pakistan is a result of this practice of consanguineous marriage. In our own country too, the custom of marrying the children of maternal or paternal siblings is found in many communities. In those communities, just like the high rate of diabetes seen in Pakistan, other genetic diseases have also been observed. Such practices still exist in some Muslim countries. As knowledge about genetics increases, this practice is found to be decreasing. Even if consanguineous marriage occurs, the practice of testing DNA before marriage to avoid genetic diseases that could arise from the expression of recessive alleles has increased.

The mismatch in the coordination of dominant-recessive genes doesn’t only happen among relatives; the danger of recessive alleles matching and showing such genetic diseases exists in others too. Facilities are now available for everyone trying to have children to test if genetic diseases might occur. Furthermore, if a possibility of such genetic diseases is seen in unborn children, new technologies like CRISPR have arrived to protect them, which can remove those mutations in the alleles.

The lesson from the Valley of the Kings to the courts of Europe is clear: biological isolation is a path to extinction. While our ancestors viewed the mixing of bloodlines as a dilution of purity, nature views it as an infusion of strength. The genetic diversity we surrendered in the name of tradition- whether for a crown, a caste, or a clan- is the very armor we need to survive as a species. By prioritizing the “purity” of the past, we have inadvertently mortgaged the health of our future.

Today, we stand at a crossroads where ancient custom meets modern science. We no longer must blindly repeat the mistakes of the Pharaohs or the Habsburgs. Whether through the widening of our social circles to embrace those outside our narrow communities, or through the precision of modern genetic screening, we have the power to dismantle these self-imposed boundaries.

To ensure the longevity of our descendants, we must learn to value the resilience found in diversity over the fragile illusion of purity. The walls of the genetic prison must be broken, not reinforced.

Leave a comment