Lobsters exhibit negligible senescence, defying the decay that defines human aging. Yet their secret- unrestricted telomerase- reveals a fatal paradox: the same fuel for their longevity acts as a driver for cancer in our complex bodies. Aging is an unavoidable cost of multicellularity- a compromise evolution made to maintain order among trillions of cells.

The Biological Cheat Code

Not long ago, the rocky coasts of New England were so thick with lobsters that early settlers described them washing ashore “in piles two feet deep.” Lobsters, called cockroaches of water were used by Farmers as fertilizers. They were so abundant that servants and prisoners complained of being fed lobster too often. Today they are vanishing from the very waters that once brimmed with them, pushed steadily northward by warming seas and centuries of human appetite.

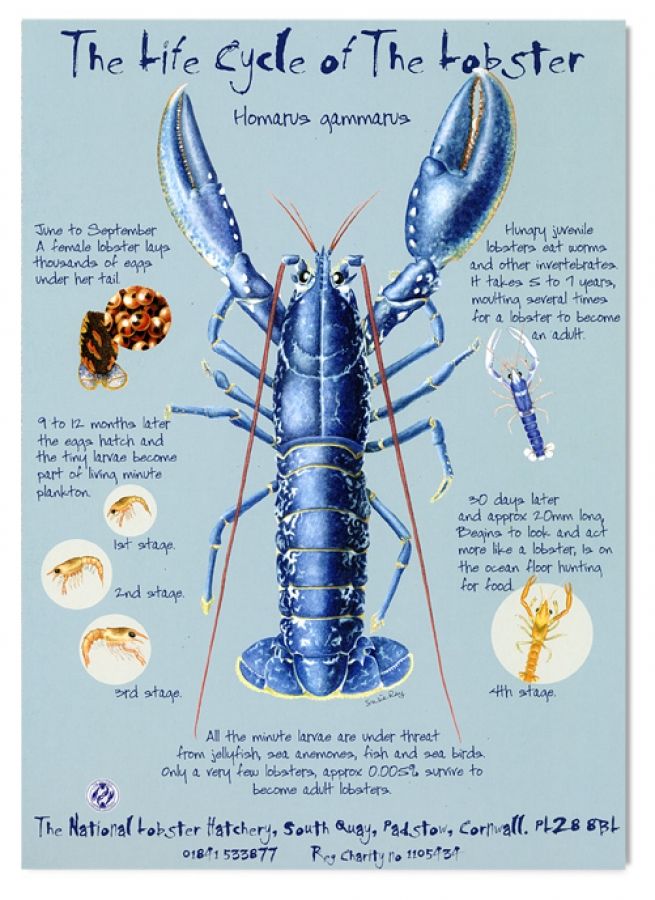

What makes their decline even more poignant is this: lobsters may be the closest thing the animal kingdom has to a biological cheat code. If you plucked a century-old lobster from the deep and compared it to one only a decade old, you’d find no obvious functional difference. Lobsters, after all, are among the small group of animals that show negligible senescence- they do not seem to age in the usual sense. Their muscles retain strength. Their reproductive output does not taper with time. Their mortality rate does not climb with each passing year.

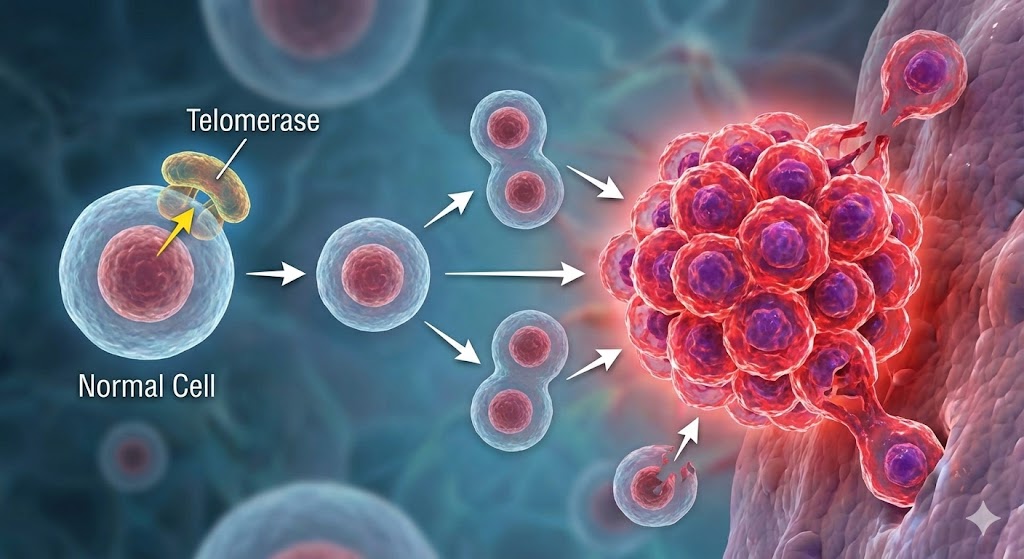

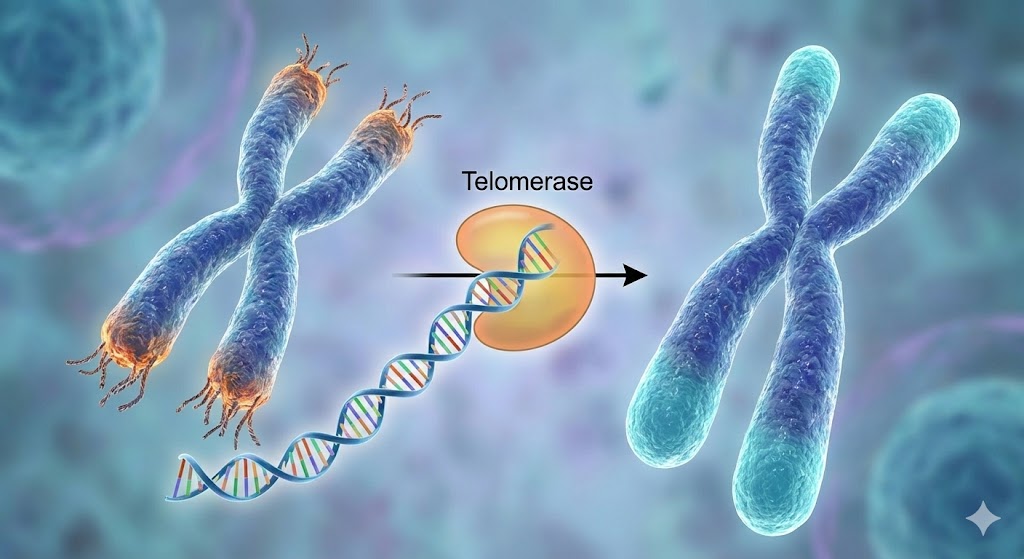

Much of this seeming defiance of aging depends on an enzyme that humans possess but tightly restrict telomerase, the ribonucleoprotein that extends telomeres. Without it, cells could divide endlessly, accumulating mutations until one slips its restraints and becomes a malignant imitator of immortality: cancer.

The Telomere Trap

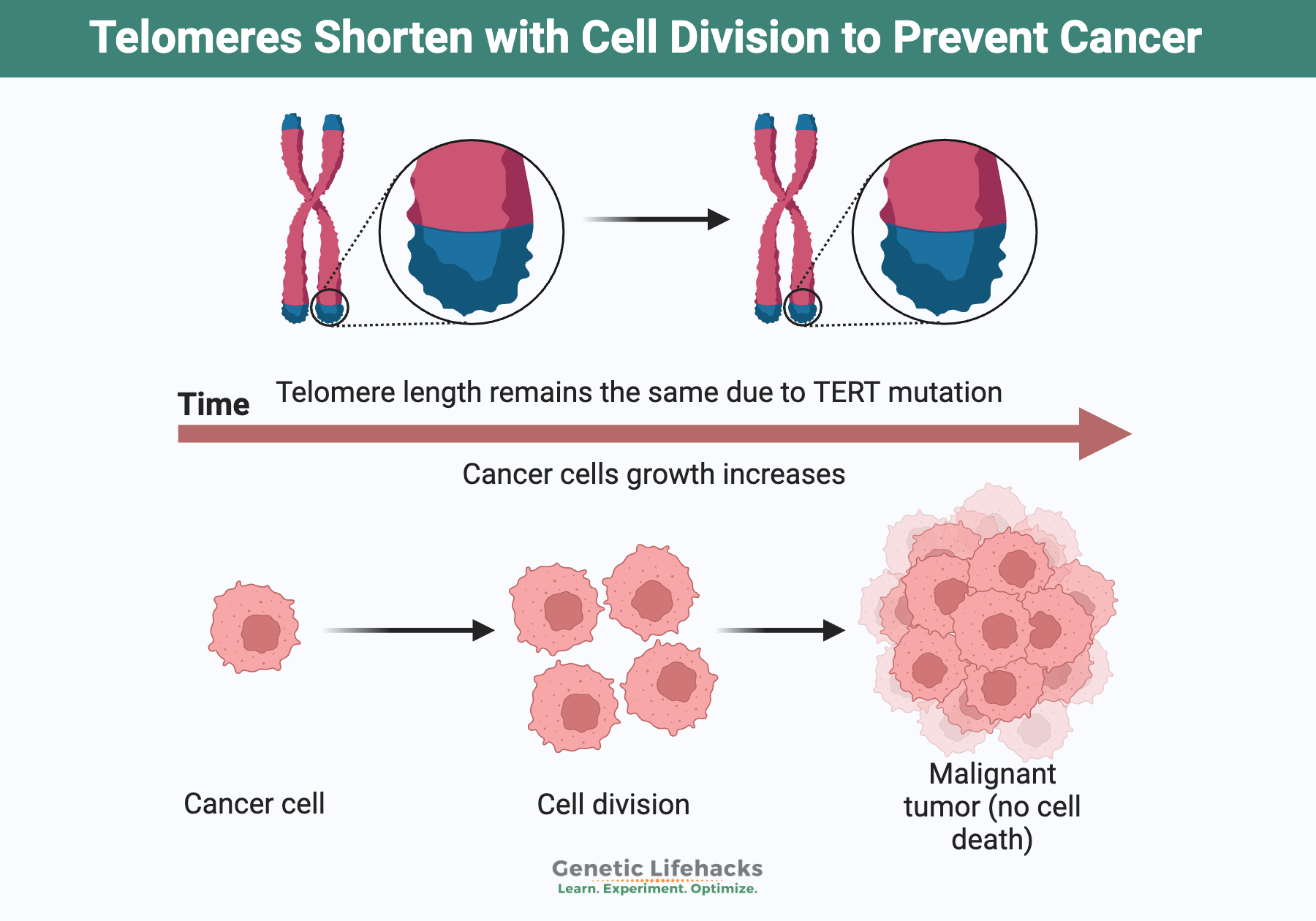

Telomere shortening is our species’ compromise: a controlled path to aging in exchange for a reduced risk of catastrophic cellular takeover. In most animals, the ends of chromosomes shorten every time a cell divides; when the protective telomeres become critically short, the cell enters a permanent arrest known as replicative senescence. In humans and most other animals, telomerase is active only in germ cells, stem cells, immune cells and approximately 90% of cancers.

Lobsters, however, keep telomerase active across most of their tissues throughout life. That simple difference means their telomeres do not shorten measurably with age. Their cells do not encounter the DNA-damage alarms that force ours into replicative senescence; their somatic cells do not hit the Hayflick limit; and their stem-cell pools do not dwindle. In molecular terms, they have sidestepped one of the most universal triggers of aging.

Yet lobsters are far from immortal. They simply die from everything except aging. Their exoskeleton grows thicker, requiring greater energy to shed. The metabolic load increases nonlinearly with size. Their immune system becomes less efficient at clearing pathogens after successive molts. Death comes not from senescence but from biomechanical limits, metabolic constraints, and ecological pressures. Negligible aging does not guarantee immortality- it merely changes the mechanism of death to the larger forces of environment and physiology.

The Cancer Compromise

But the real value of the lobster anecdote lies not in its supposed immortality- it lies in the contrast with us. Humans age for reasons that are deeply embedded in the architecture of multicellularity, and understanding why we cannot simply “keep dividing” like a lobster requires tracing the molecular compromises that hold our bodies together.

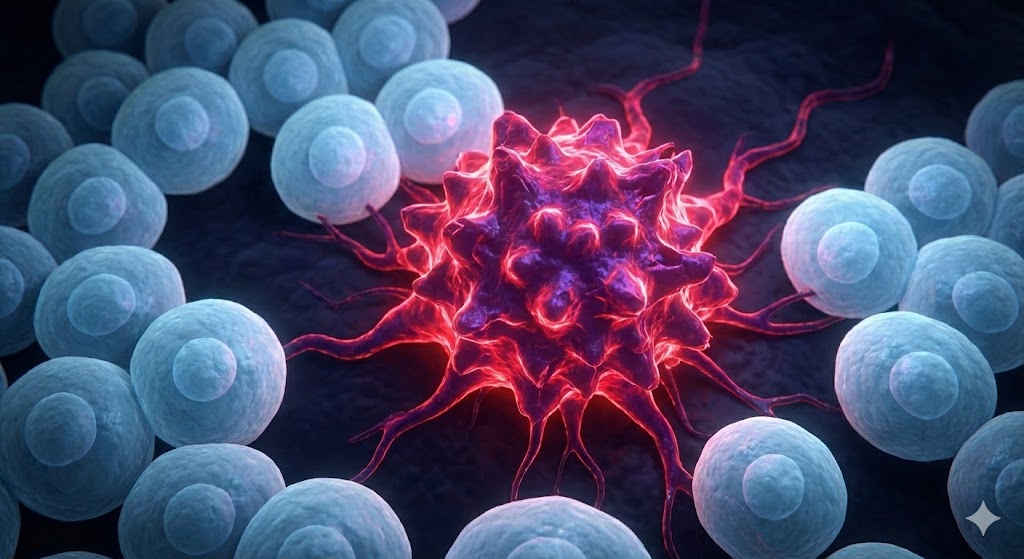

Multicellular organisms are not just collections of cells. They are cooperatives, held together by a tenuous agreement that no cell will pursue its own immortality. Each cell must accept limits: it must divide only when asked, repair itself faithfully, and, if damage accumulates, remove itself for the good of the whole. A cell that ignores DNA damage signals, reactivates telomerase, and proliferates freely becomes a cancer.

Telomere shortening is part of that enforcement system. In humans, nearly every somatic cell carries a built-in replication limit. Each time DNA is copied, the very ends of chromosomes- the telomeres- lose a few dozen nucleotides. The sequence TTAGGG repeats disappear little by little because our DNA polymerase cannot fully replicate the extreme ends of chromosomes. These repeating sequences do not code for genes; instead, they serve as buffers so actual coding DNA is preserved.

When those telomeres grow critically short, the chromosome ends resemble broken DNA. To prevent this, organisms evolved layers of surveillance: p53 and its downstream effectors sensing broken DNA, ATM and ATR kinases pausing the cell cycle, epigenetic remodeling of the TERT gene, and ultimately senescence acting as an irreversible stopgap when all else fails.

Telomere shortening is not a flaw but a safeguard that evolution chose, because unrestricted replication in complex bodies is far deadlier than aging itself. In youth, this is protective. It stops precancerous cells before they ever become a threat.

Human telomerase could, in theory, fix this. This enzyme can rebuild telomeres and allow persistent self-renewal. But in most human tissues, telomerase is tightly silenced. Only stem cells, germ cells, and certain immune compartments have enough activity to maintain long-term replicative capacity. The suppression of telomerase in ordinary tissues is not a mistake; it is a barrier against malignant immortality.

Could humans simply copy the lobster and reactivate telomerase broadly? Nature has already experimented with this answer, and we call that experiment cancer. More than four out of five human cancers unlock telomerase by mutating or epigenetically reactivating the TERT gene.

Telomere maintenance, in our evolutionary context, is less a recipe for vitality than a step toward malignant immortality. Our bodies use telomere shortening as a surveillance mechanism is therefore an evolutionary bet: better to age predictably than to risk uncontrolled proliferation.

The Burden of Maintenance

Senescence or Aging, in this light, is not a simple deterioration but a complex shift in the body’s internal equilibrium, where protective mechanisms begin to work at cross purposes. Senescence, though protective early in life, becomes corrosive when it accumulates. A senescent cell is not merely idle- it leaks inflammatory molecules, growth factors, and matrix-degrading enzymes, what biologists call the SASP (senescence-associated secretory phenotype). This was useful in youth, when rapid wound healing and the elimination of damaged cells outweighed any long-term cost. But as the immune system’s capacity to clear senescent cells wanes with age, tissues are bathed in a chronic inflammatory milieu.

Telomerase alone cannot correct this drift. Were humans to reactivate telomerase broadly, we would not emulate lobsters so much as our own cancers, which activate telomerase through promoter mutations or epigenetic escape. Telomeres are only one piece of the broader biological clock. Proteins misfold and aggregate despite chaperone systems; DNA acquires damage that even the most vigilant repair pathways cannot always mend; mitochondria mutate their genomes at rates many times higher than the nucleus; immune cells lose their youthful repertoire; and tissues such as brain and heart, built from long-lived, non-dividing cells, accumulate microdamage that cannot simply be diluted by fresh divisions. Even the most perfect telomere maintenance cannot solve these problems.

Lobsters keep telomerase running in many tissues, but that simply delays one class of failures while exposing them to others- metabolic strain, infectious load, and the physics of growing indefinitely in a hard exoskeleton.

The Regenerative Road Not Taken

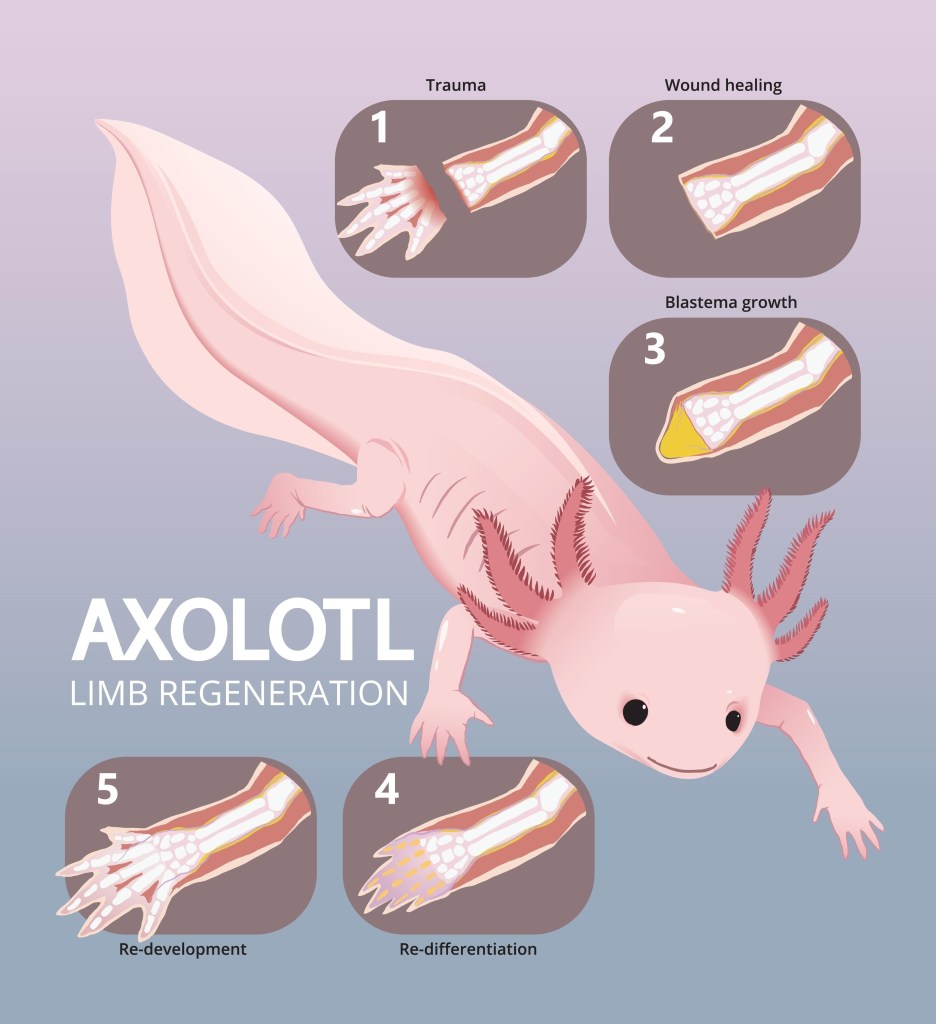

That contrast becomes more striking when we consider another creature often labeled “regenerative”: the salamander. Unlike lobsters, salamanders do experience aging in many ordinary ways- they accumulate mutations, suffer metabolic slowdown, and face ecological hazards. But they possess a talent that humans lost long ago: they can regenerate complex structures- full limbs, spinal tissue, parts of their heart and eyes- without fibrosis and without triggering runaway cancer.

When a salamander regrows a limb, its cells temporarily re-enter a more flexible, embryo-like state. They proliferate, but with exquisite control, preserving positional information and halting division exactly when the structure is complete. This regeneration depends on robust anti-inflammatory signaling, efficient DNA repair, and epigenetic plasticity that adult human tissues mostly lack.

Salamanders and lobsters offer two different biological strategies that diverged from our own. One maintains telomerase activity and continuous turnover; the other maintains regenerative flexibility and precise control. Humans, meanwhile, evolved a different equilibrium- one that trades longevity of individual tissues for the stability of a complex, cancer-resistant body. We traded continuous repair for tighter control, and in doing so accepted senescence as the price of maintaining order among trillions of potentially rebellious cells. What appears like immortality is just a shift in the balance of vulnerabilities.

A Narrative That Ends

The deeper lesson is that multicellularity itself is the constraint. A single-celled organism can divide forever if conditions allow. But once cells agree to specialize, cooperate, and suppress their individual replication for the good of the whole, immortality becomes more complicated. The body must police its cells, and every policing strategy- telomere shortening, senescence, apoptosis, DNA checkpoints- extracts a long-term cost.

Lobsters remind us that even defeating cellular aging cannot defeat the physics of life. Salamanders remind us that regeneration does not guarantee endurance. And humans remind ourselves, again and again, that aging is not a flaw in our design but part of what made the design possible in the first place.

When we speak of immortality, we usually imagine it as something individuals might grasp if only, we could fine-tune a few genes or strengthen a few cellular pathways. But biology, especially the biology of multicellular life, tells a different story. Immortality belongs not to individuals but to lineages. Your somatic cells are designed to serve a narrative that ends; your germline cells are designed to continue a story written more than three billion years ago.

Every human death is thus both an ending and a handoff. In safeguarding the body from the cancerous ambitions of its own cells, evolution traded away the possibility of endless life. The price of being a multicellular being- of having hearts and brains and the collaborations of trillions of specialized cells- is accepting that those same collaborations require a limit.

Lobsters, in the end, are not templates for our future but mirrors for our limitations. They remind us that we are not held back by a single missing enzyme or a single faulty pathway. We age because our entire architecture is built to balance growth with restraint, renewal with surveillance, longevity with safety.

Evolution shaped us not for endless life, but for functional life long enough to reproduce and care for offspring. Immortality, in other words, was never part of the design. It was the compromise that kept the peace.

Leave a comment