We have always been taught a specific narrative: the stomach was filled first, and only then did humanity remember the Divine. But the 13,000-year-old ruins in Turkey have flipped this script entirely. The discoveries at Göbekli Tepe and Boncuklu Tarla prove that the bond that tied humanity to a single place was not the plow, but faith. This journey-spanning 13,000-year-old sewerage systems, decorative jewelry, and body piercings-reveals that the “Egg of Faith” was laid long before the “Chicken of Civilization” ever hatched.

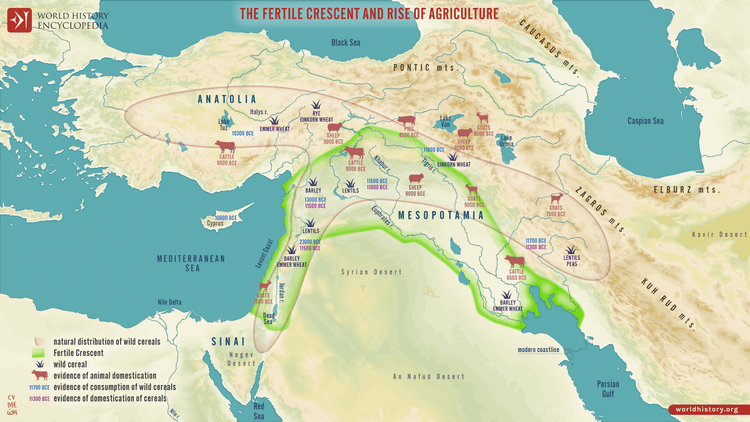

Map showing the location of Göbekli Tepe and Boncuklu Tarla within the ancient Fertile Crescent.

The Chicken, the Egg, and Our Illusion

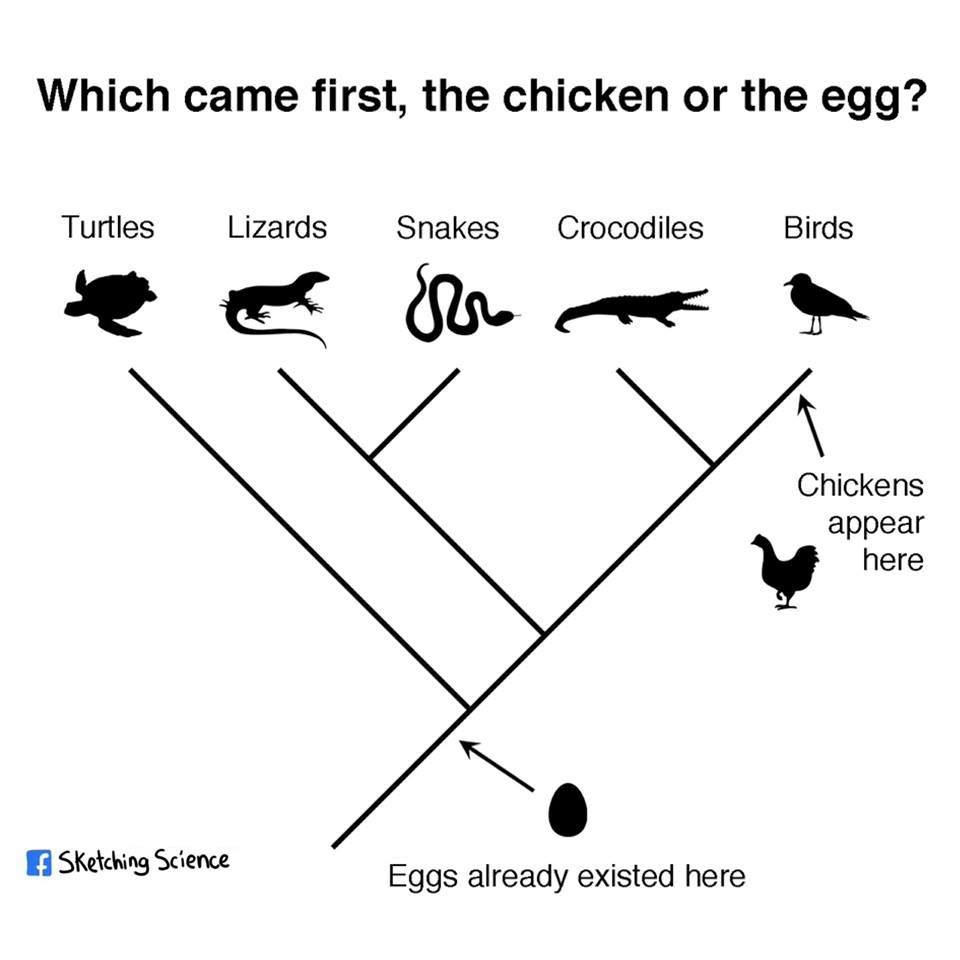

“Which came first: the chicken or the egg?” We are all familiar with this riddle. However, in our search for a simple answer, we often embrace a misunderstanding. To many, the logical answer is the chicken, because an eggshell cannot form without one. We know that the proteins required to build the outer shell, such as Ovocleidin-17, are found only in the body of a hen. Based on this, we conclude that since an egg cannot exist without a chicken, the chicken must come first.

This “simplicity” is our illusion. We must view this question through the lens of evolutionary biology rather than a single moment in time. Science shows us that the egg is an ancient structure, older than dinosaurs and far older than the chicken. The “chicken” is merely a name-a classification-that appeared only a few thousand years ago. It did not suddenly manifest; it is the result of a transformation that slipped gradually through thousands of generations.

The evolutionary perspective: the egg pre-dates the modern chicken by millions of years.

The Evolution of Language and Biological Continuity

This becomes clearer when compared to the history of language. Latin did not suddenly become Italian overnight. The first people to speak Italian did not learn it from parents who spoke Italian; they spoke a form of Latin that was shifting. Latin changed slowly: sounds morphed, grammar slipped, and words took new forms until, one day, we began to call it “Italian.” The parents of the first Italian speaker were not “Italian,” yet we call their offspring so today. The name came later; the change came first.

The story of the chicken is the same. The biological method of making an egg existed for millions of years. A small biological slip-a microscopic mutation-occurred within an egg during a mating between two “proto-chickens.” The mother was “almost” a chicken; the egg was “almost” a chicken egg. The method was old, but the embryo inside crossed a tiny biological boundary that we, looking back, named the “chicken.” The egg is a vessel of continuity where the new is born within the old.

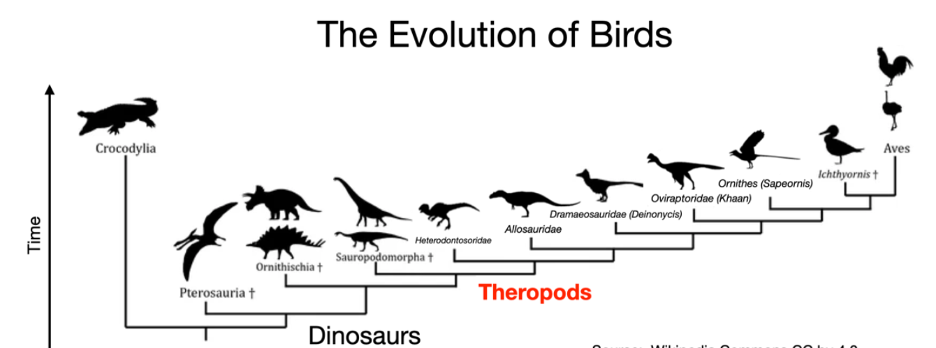

A visual representation of the evolutionary transition, showing that egg-laying is an ancient biological process.

The Debate of Civilization: Agriculture or Religion?

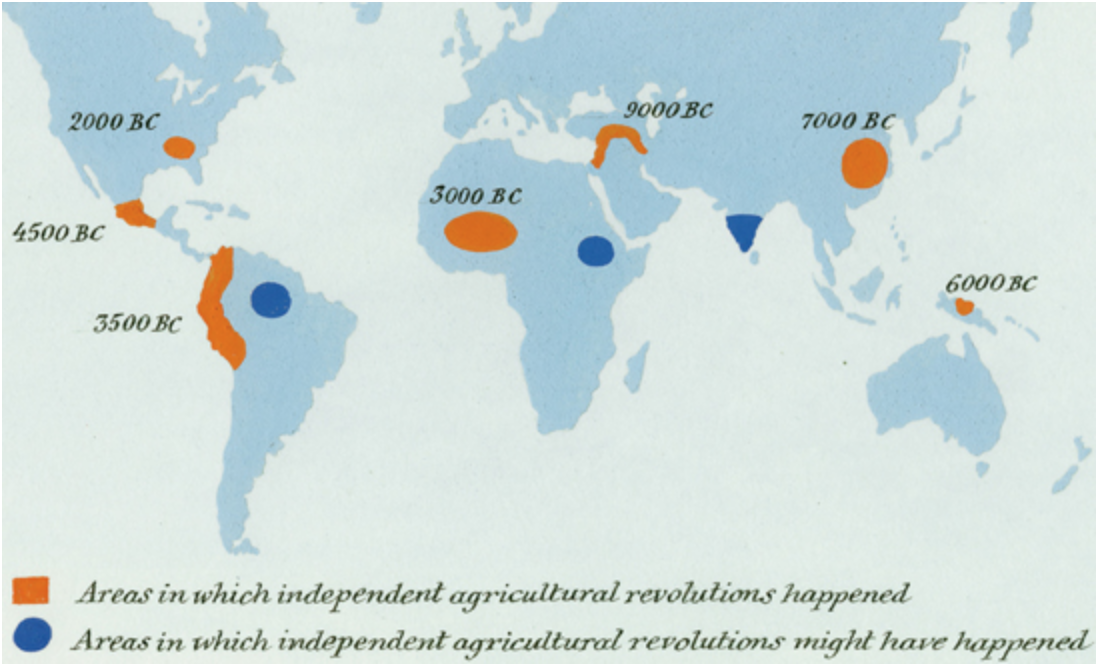

This same logic applies to the debate over the origins of civilization: Did agriculture come first, or did faith? Like the chicken and the egg, this question haunts archaeologists. We treat “farming” or “religion” as fixed starting points, but civilization was not an instant invention. It was a process taking shape within ancient practices and changing lifestyles.

Traditional maps placed the origin of civilization in the “Fertile Crescent”-the arc stretching across modern-day Iraq, Syria, and Iran. However, recent excavations have pushed this story north, into the Southern Anatolia region of Turkey. Thirteen thousand years ago, the people of the Anatolian highlands were “complex gatherers.” They hunted and gathered wild grains, and while they moved with the seasons, they returned to the same sites repeatedly. It is here, around 11,000 BCE, that we find the oldest evidence of a transition.

The Invention of Agriculture and the Role of Female Consciousness

As the world emerged from the Ice Age and entered the Holocene epoch, temperatures rose and land became fertile. During this time, gatherers-specifically women-noticed something revolutionary: where wild seeds fell and gathered, new plants grew more vibrantly the following year.

Common historical knowledge suggests the beginning of farming did not happen all at once. Agriculture was not a laboratory experiment; it was the product of thousands of years of subtle observation and patience, the credit for which belongs primarily to women. While men traveled for the hunt, women gathered tubers and grains near the camp, observing the plant life cycle. They realized that seeds falling near organic waste (fertilizer) flourished.

This “female consciousness”-the realization that it was safer to plant and protect seeds near one’s own hut than to wander the forest-was the true spark of agriculture. By selecting the best seeds over generations, they transformed wild wheat into domestic wheat. The discovery of the world’s oldest wheat DNA near Mount Karacadağ confirms this. When man understood the relationship between seed and manure, the human courage to take the cycle of nature into one’s own control began. But even this “Farming First” narrative is incomplete.

Göbekli Tepe: When Faith Led the Plow

For a long time, historians believed a specific narrative: first people learned to farm, then they made permanent houses, and when the store of grain was full and they became leisured, only then did they make temples and religion. In other words, “First the stomach was filled, then God was remembered.”

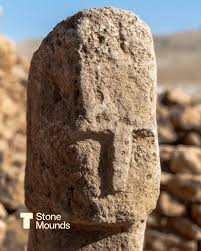

In 1994, Klaus Schmidt’s excavation of Göbekli Tepe shook this foundation. This 12,000-year-old site is the world’s first temple and the first “3D” expression of human consciousness. Its massive T-shaped limestone pillars represent faceless human-like deities. The carved hands and meditative postures show that humans were capable of symbolic worship long before they were farmers. In these limestone pillars, we find scorpions, foxes, and lions carved as if they might come right out of the stone, showing an advanced understanding of nature.

The monumental T-shaped pillars of Göbekli Tepe, featuring intricate animal reliefs.

Göbekli Tepe was built by hunter-gatherers. No permanent houses or farming tools were found there. However, to feed the thousands of workers and pilgrims gathered to build and worship, wild food was insufficient. The pressure to feed this massive spiritual gathering forced humans to domesticate grains like wheat and barley. The reality is: The desire to build the temple made us into farmers.

Boncuklu Tarla: The First Foundation of Civic Life

For a long time, we believed that the chicken of human civilization was born from the egg of ‘farming.’ But the discovery of Göbekli Tepe showed a different egg: the egg of faith. The work of making man stable in a community was not done by the plow, but rather by a shared belief in an invisible power.

If Göbekli Tepe pushed history back, Boncuklu Tarla (discovered in 2008) pushed it even further. While Göbekli was primarily a ritual center, Boncuklu Tarla had already become a full-time human settlement. Dating back 13,000 years, it was a thriving community long before Göbekli Tepe reached its peak more than a thousand years later.

At Boncuklu Tarla, we find permanent circular houses and early prototypes of the ‘T’ shaped pillars. This shows that the massive structures of Göbekli Tepe were not made overnight but were the product of centuries of human labor. Perhaps the most shocking find was a systematic sewerage system. To build stone drains to keep a settlement clean 13,000 years ago is staggering. It proves that we were thinking about community health and urban planning while we were still hunters.

Identity and the Origin of Ritual

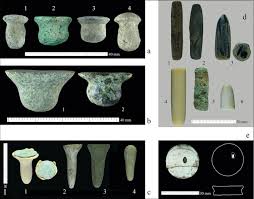

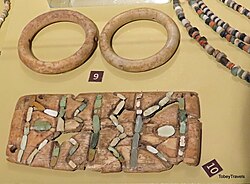

The residents of Boncuklu Tarla were very conscious of their ‘self’ or identity. Boncuklu Tarla literally means ‘Field of Beads.’ In this site, spread over thirty acres, more than one hundred thousand decorative ornaments made from limestone, obsidian, and bone have been found.

Latest research from 2024 has shown that the people there practiced the ritual of ‘piercing.’ As they began living in communities, humans needed more than just food and water; they needed identity and stability. Stone ornaments found near the ears and lower jaws of skeletons provide the first evidence of physical modification. These were not just art; humans had begun to signal social status and individual existence.

Archaeological finds from Boncuklu Tarla, including circular house foundations and stone beads.

We didn’t settle down because we had too much food; we settled because we wanted to be near those beads, near our buried ancestors, and within the safety of an organized community. The “ideal” of how life should be lived came before the “principle” of how to farm. The search for an ‘ideal’ brought us to Göbekli Tepe, but the egg of ‘principle’ had been laid in Boncuklu Tarla much earlier.

Conclusion: The Continuous Transformation of Civilization

If Göbekli Tepe is the “Zero Point” of religion, Boncuklu Tarla is the “Zero Point” of civic life. Civilization was not a sudden explosion; it was the gradual expansion of consciousness from the beads of Boncuklu Tarla to the stone gods of Göbekli Tepe.

Faith, farming, and consciousness are intertwined. The “Chicken” of civilization was not born from a single egg, but from a contract between hunger, identity, and collective responsibility. Our modern jewelry reflects those 13,000-year-old beads; our city engineering follows the footprint of those first sewers.

The answer to the riddle is: Change came first. Agriculture, religion, and cities are just names for a restlessness and a dream that were already there. We are still a link in that same transformation that began in the hills of Anatolia.

Leave a comment