“A recent breakthrough in Spain has achieved the ‘holy grail’ of oncology: complete tumor regression in pancreatic cancer models using a novel ‘triple blockade.’ But before we celebrate a cure, we must confront a stark historical truth: science cures mice thousands of times, yet human biology is far less forgiving.”

A recent report from the Spanish National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO) has sent a current of genuine excitement through the oncological community. In the high-stakes world of cancer research- where progress is usually measured in cautious percentages rather than dramatic reversals- the findings from Madrid stand out as unusually bold. The researchers reported the complete regression of pancreatic cancer in animal models, with no recurrence observed over the duration of the study– an outcome often described as the holy grail of oncology.

To grasp the real significance of this achievement- and to avoid the familiar cycle of inflated hope followed by public disappointment– we must set aside the sensationalism of headlines and examine the findings through the lens of scientific reality. The news is not that cancer has been cured in humans. It is that researchers have finally identified a map: a coherent, testable strategy that could, largely and eventually, point the way forward.

The Science of the “Triple Blockade”

Pancreatic cancer, Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), is among the deadliest of human cancers not because it is fast, but because it is adaptive. It behaves less like a malfunctioning machine and more like an evolutionary system- capable of rerouting signals, activating backups, and surviving assaults that would cripple less sophisticated tumors. For decades, researchers have tried to shut down the molecular pathways that fuel PDAC growth, only to watch the cancer find another way out.

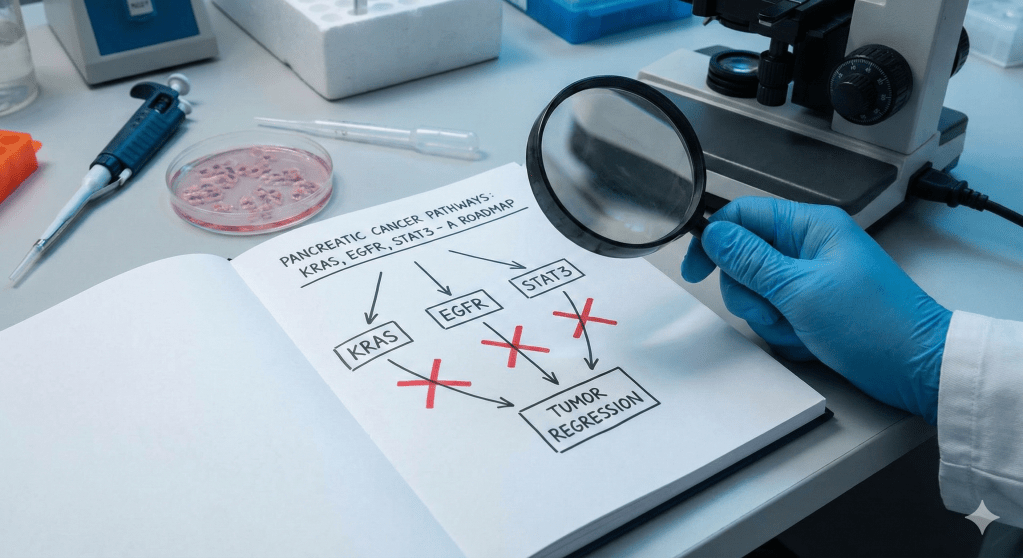

The CNIO team approached this problem through the framework of “synthetic lethality”: the idea that while a tumor may tolerate the loss of one or even two critical pathways, it cannot survive the simultaneous disruption of several interdependent systems. Their insight was not merely to block pancreatic cancer’s primary engine, but to also shut down its ignition switch and its escape route at the same time.

They focused on three signaling nodes: KRAS, the driver mutation present in the vast majority of pancreatic cancers; EGFR, an upstream signaling molecule that acts as an activator; and STAT3, a pathway that often compensates when the others are inhibited. Using a combination of genetic manipulation and pharmacological inhibition, the researchers suppressed all three pathways simultaneously in mouse models.

The results were striking. Tumors did not merely shrink; they disappeared. Just as importantly, they did not recur. By collapsing all three pillars at once, the strategy appeared to eliminate the cancer’s ability to adapt-something single-agent therapies have failed to achieve for decades. In the controlled environment of the laboratory, the approach was biologically elegant and unusually complete.

The Mouse as a Filter, not a Finish Line

This is the point at which the public narrative often departs from reality. When people hear the phrase “cancer cured,” they imagine a patient leaving a hospital cancer-free. In this case, the cure applies to a mouse- and that distinction is not a footnote. It is the central fact.

Science cures cancer in mice thousands of times. Historically, roughly ninety percent of these apparent cures fail when translated into human trials. This failure rate does not reflect sloppy research; it reflects biology. Laboratory mice are genetically uniform, engineered to develop cancer in predictable ways, and treated at early, controlled stages of disease. Their immune systems are comparatively pristine, unshaped by decades of environmental exposure, metabolic stress, or chronic inflammation.

Mouse models are not meant to predict success in humans. They are meant to eliminate ideas that have no chance of working at all. In that sense, they function as a ruthless filter rather than a finish line. The CNIO study has passed that filter convincingly. But passing the filter is not winning the race-it is merely earning the right to start it.

From Genes to Drugs: The Hard Translation

The most difficult challenge now is converting the genetic interventions used in mice into therapies that humans can actually tolerate. You cannot simply “delete” the KRAS gene in a human being without catastrophic consequences. Instead, clinicians must rely on a “cocktail” of drugs that inhibit these proteins- a strategy that is less precise and far more toxic.

The CNIO team has outlined a plausible pharmacological strategy for human trials. It begins with RMC-6236, a new class of inhibitor designed to suppress the historically “undruggable” KRAS mutation. This must be combined with Afatinib, a drug already approved for lung cancer that targets EGFR, and finally SD36, a degrader for the STAT3 pathway.

While the chemistry is sound, the biology is perilous. The immediate obstacle is cumulative toxicity. All three of these targets- KRAS, EGFR, and STAT3– are also used by healthy cells for maintenance and immune function. A mouse can survive weeks of aggressive pathway suppression; a human patient must survive months of it. Blocking EGFR and STAT3 simultaneously often produces severe skin, gut, or immune toxicities. If these side effects force doctors to pause treatment, the window of opportunity closes, and the cancer recovers.

The Graveyard of Mouse Cures

History provides ample reason for caution. In 1998, angiogenesis inhibitors like Endostatin captivated the world by starving mouse tumors of their blood supply. A Nobel laureate famously predicted a cure within two years. But in humans, tumors proved resourceful, finding alternative vascular routes, and the “cure” never materialized as promised.

A decade later, the “Hedgehog” pathway offered an even starker lesson for pancreatic cancer. In mice, blocking this pathway melted away the dense scar tissue surrounding the tumor, allowing chemotherapy to penetrate. It seemed perfect. But in human trials, the results were disastrous. It turned out that the scar tissue wasn’t just a wall keeping medicine out; it was a prison wall keeping the cancer in. By melting it away, the drug inadvertently allowed the cancer to spread faster. The trial was halted early because patients on the experimental therapy were dying faster than those on the placebo.

The Long Road Through the Valley of Death

The transition from a successful animal study to a clinical therapy is a process often described in the pharmaceutical industry as the “valley of death.” The CNIO findings mean that this approach is now scientifically robust enough to justify risking years of labor and millions of euros on clinical trials.

The immediate next step is not a prescription, but toxicology. Researchers must determine if blocking KRAS, EGFR, and STAT3- proteins that healthy cells also rely on for survival- will kill the cancer without killing the patient. If the toxicity profile is manageable, the drug moves to Phase I trials to establish safety in a small cohort of humans. Only then does it proceed to Phase II to test for efficacy, and finally Phase III, where it must prove itself superior to the current standard of chemotherapy.

Even in a best-case scenario, where every phase succeeds without delay, this timeline spans eight to ten years. This is the messy, slow, and expensive reality of drug development.

Conclusion: What Success Actually Looks Like

The danger of stripping away this context is not merely scientific misunderstanding-it is the slow erosion of public trust. Repeated cycles of “Cancer Cured” headlines followed by real-world disappointment encourage the belief that cures are being hidden or that scientists are incompetent.

The reality is less dramatic but far more honest. Science advances unevenly. It is slow, expensive, risky, and littered with dead ends. The CNIO study is a genuine triumph because it clarifies the problem. It tells us which three doors must be locked simultaneously to trap one of the deadliest cancers we know. What remains is the harder task of building locks that fit the doors of human biology.

This discovery is not a miracle. It is something better: a well-drawn map. It justifies the risks of the next decade of clinical trials, even as it offers no guarantees. In the hard reality of oncology, that is what real progress looks like.

The original research paper can be found here.. A targeted combination therapy achieves effective pancreatic cancer regression and prevents tumor resistance

Leave a comment