“If you’re going to San Francisco / Be sure to wear some flowers in your hair.

If you’re going to San Francisco / You’re going to meet some gentle people there.”

~Scott McKenzie, San Francisco (1967)

In the summer of 1967, the air was thick with incense, rebellion, guitars, and drums. A strange and beautiful migration was underway. Young people from across America poured into San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury neighborhood. Holding peace signs, dressed in tie-dye, humming Jefferson Airplane and Dylan, quoting Rumi, Ginsburg, and Ram Das. Chanting “Turn on, tune in, drop out,” they all came chasing free spirit. That Summer- now immortalized as the Summer of Love- birthed a movement that would ripple across continents. The Hippies.

Who were the Hippies? If anyone asks you, you will probably say that they were the strangely clothed young people with long hair and unshaved beards, beads; flowers attached to their tie-dyed shirts, hazy eyes buzzed on marijuana, acid and other drugs. If you know a little more, you’ll think of them wanting a world where people can live together without fighting one another, singing songs of war and peace, with rage against age-old systems.

From my childhood, I have heard stories about the Hippies and the Magic Buses they traveled to Kathmandu with. Stories from many fathers and uncles, who were part of the generation, who started smoking weed or started wearing jeans and bought guitars and dreamy jackets after meeting with the Hippies in the early 70s.

Roots of the revolution: Thoreau to the Beat Generation

The hippie movement didn’t begin with guitars and acid trips. Its roots go deeper- into the pages of Thoreau’s Walden. “Simplify, simplify”; Thoreau left society to live in a cabin in the woods near Walden Pond, seeking a life of simplicity, self-reliance, and harmony with nature- a foundational hippie value. His Civil Disobedience taught a future generation to simplify, resist, and listen to the language of trees. The Beat poets- Kerouac, Ginsberg, Burroughs- picked up the torch in smoky cafes of New York and sought enlightenment through Zen, Jazz, and the open road. Beatniks, thus, became the spiritual ancestors of the hippies. Dylan’s “Times They Are-A Changin” provided the necessary slogan.

By the early 1960s, the stage was set. That Beatnik spirit fused with the civil rights movement, anti-war protests, and a growing mistrust of government following the Cuban Missile Crisis and Kennedy & King assassination. Youth responded by embracing an idealistic new world order, a better society. They embraced psychedelics, free love, communal living, and the wisdom of the East. The hippies were not simply escapists; they were idealists rebelling against a segregated and mechanized world whose existential searches ultimately led, many, to the mystical paths of the East.

Music: Shaped the Movement and Shocked the world

Music was the movement’s heartbeat. Scott McKenzie’s San Francisco played like a sacred invitation. “Be sure to wear some flowers in your hair,” he sang, inviting the world into a moment of collective transcendence. The Beatles came up with Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and declared “All You Need Is Love” live on global television. “A splendid time is guaranteed for all,” they promised. It was a promise of freedom, a utopia of music, art, and mind expansion- a world that felt both distant and close, like a dream on the verge of becoming real.

There were Janis Joplin and the Doors, as organizers they gave free concerts in the park every day. Timothy Leary continued to chant his LSD slogan, “Turn on, tune in, drop out.” Young people from all over America started converging into a street in San Francisco, called Haight-Ashbury. They came for escape and the expansion of consciousness, for music, for peace and protest, for grass and acid. The summer of 1967 in Haight-Ashbury was about to became the “Summer of Love,” marking the beginning of the Hippie era.

It wasn’t just San Francisco that defined the counterculture in 1967. The Monterey Pop Festival, in the same summer, gave unofficial birth of the psychedelic movement. There were no Pink Floyd yet, but Grace Slick urged listeners to “choose your pills wisely”. The Animals and The Who enchanted with new music. Jimi Hendrix lit his guitar on fire, and Janis Joplin poured out her raw soul, both declaring themselves onto global stages in a way never seen before. The old guards were changing, and a new kind of music was being born.

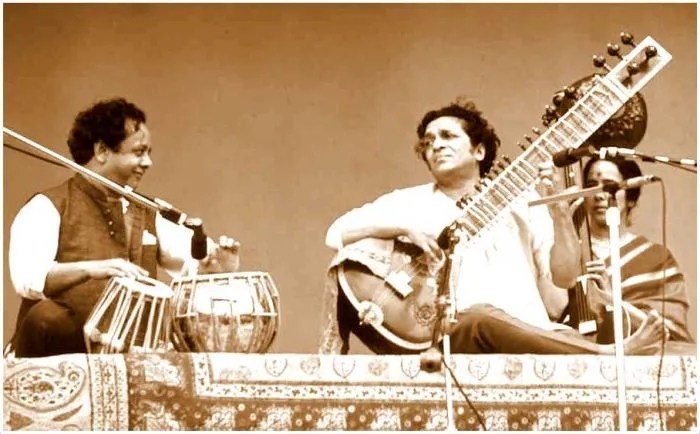

This was also the time America discovered the music of the East. On the last afternoon of the Monterey Pop Festival, Ravi Shankar enchanted the 100,000+ audience with his sitar for more than four hours, leading to a reception almost as long that the echoes still reverberate.

Woodstock: The Ultimate Expression of Peace and Protest

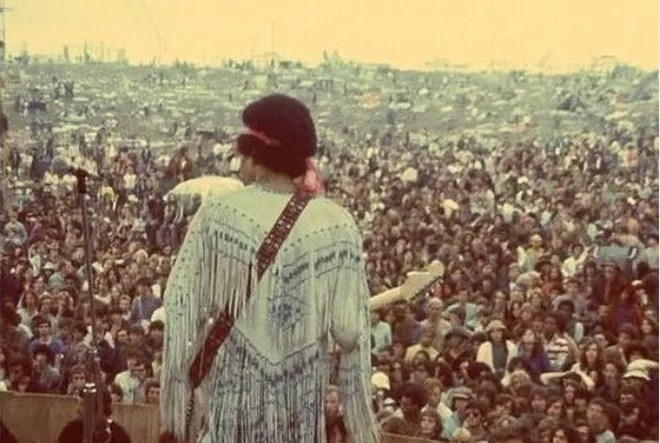

By August 1969, all these ideas collided in a way no one had expected, not least the organizers. Half a million people- musicians, activists, seekers- young people from all over America gathered on a dairy farm in Bethel, New York, for Woodstock- a festival of peace, love and music. There were no borders- only blankets, bodies, guitars, and endless smoke. For three electric days, Woodstock was a utopia. It was muddy, chaotic and peaceful, utterly human and beautiful. The hippie dream seemed like a reality, even if only for a fleeting moment.

The whole event teetered on collapse yet somehow held together to witness Woodstock’s musical heartbeat across dozens of acts, each offering their own sonic vision of freedom, rebellion, and soul. Richie Havens opened with improvised urgency, strumming “Freedom” until his fingers bled, setting the tone for what would become a 72-hour odyssey of music and mud. Santana, then a little-known band from San Francisco, delivered a volcanic performance of “Soul Sacrifice” that catapulted them into legend.

Janis Joplin treated the blues like a soul on fire, while Joe Cocker’s cover of “With a Little Help from My Friends” turned a Beatles tune into a gospel sermon. And then there was Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, nervously declaring, “This is only the second time we’ve played in front of people,” before delivering harmony that sounded like fragile prayers. The star of the show was Jimi Hendrix, arriving last, and closed the festival with a distorted, metallic version of ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’, transforming the national anthem into a song of protest, against the Vietnam War.

But Woodstock was more than just music. It was a temporary nation of barefoot idealists and muddy prophets, held together by shared hope, shared danger, and shared dreams. Joni Mitchell, who didn’t attend wrote about the festival watching it on a TV from a New York hotel room, perfectly captured the sentiment in her iconic line:

“We are stardust, we are golden / And we’ve got to get ourselves back to the garden.”

The Decline in the 70s: A Move to the East

But utopias rarely last, and that garden was never really found. The festival ended; the idealism faded. By the time the 1970s arrived, Jim, Jimi, and Janis were all dead. The new political reality of Nixon slowly replaced the dreamy haze of the 1960s. Marijuana and LSD were criminalized. The Vietnam War escalated. The War on Drugs and cultural backlash came banging. Altamont turned deadly. And what had been a movement began to feel like a memory. As the decade turned, the music, the movement, and the spirit all began to shift outwards, towards the mythical East.

The garden, it seemed, had not been regained- it had been paved over. What had been a spiritual rebellion was suddenly being sold on cereal boxes and department store racks. And so, many young Americans- disillusioned, restless, still searching- did something radical: they left. They left behind the suburbs and the strip malls and instead followed the rising sun. They turned East. Toward India, Afghanistan, and finally, Nepal. Toward mystics, mountains, and myths- into the unknown.

The Hippie Trail emerged- an uncharted route stretching from Europe to South Asia.

As the Western dream turned dystopian, a new pilgrimage emerged. They traveled along an overland route from Europe to South Asia before finally reaching Kathmandu- the last sanctuary on the road to spiritual awakening.

From London to Kathmandu, the Hippie Trail and Magic Bus became a rolling confession, a drifting escape, a rite of passage. They rode the Magic Bus- a fleet of rickety, colorfully painted coaches that offered rides from London all the way to Kathmandu for just a few dollars. The path:

Amsterdam → Istanbul → Tehran → Kabul → Delhi/Varanasi → Goa → Kathmandu.

While we think of a particular Volkswagen as the Magic Bus, it wasn’t just one specific bus, but rather a symbol of the journey- slow, chaotic, but full of adventure.

In Tehran, Kandahar, and Islamabad, they experienced Islamic culture that no longer exists today. In Goa, they danced to sitars and the sea. In Rishikesh and Varanasi, they chanted with monks. But in Kathmandu, they found the mythical last stop. In place of Woodstock crowds, there were temple bells, smoke from incense and hashish, and silent meditations. Some came chasing nirvana, other narcotics, most sought escape. The East promised what the West had failed to deliver: peace, mysticism, and freedom- real or imagined.

Kathmandu: A Himalayan Shangri-La as the last stop.

Before the Magic Bus began to arrive in droves, Kathmandu in the 1960s was already a whispered legend among seekers and drifters. A handful of adventurers- explorers, artists, musicians, poets- made their way across the Himalayas, drawn by tales of a medieval city untouched by time, where the temples outnumbered cars, and marijuana grew wild on the riverbanks.

Allen Ginsberg, who visited in 1962, wrote of Kathmandu as a “pure land” of mystics and mandalas. There are stories of Jimi Hendrix jamming in Pashupati and in Mustang. Janis Joplin is said to have meditated in Nagarkot and mentions Kathmandu in her song, Cry Baby. John Lennon wrote about “Yellow idol in the North of Kathmandu” on Nobody Home, a song he wrote following their travels to India and Nepal in 1965.

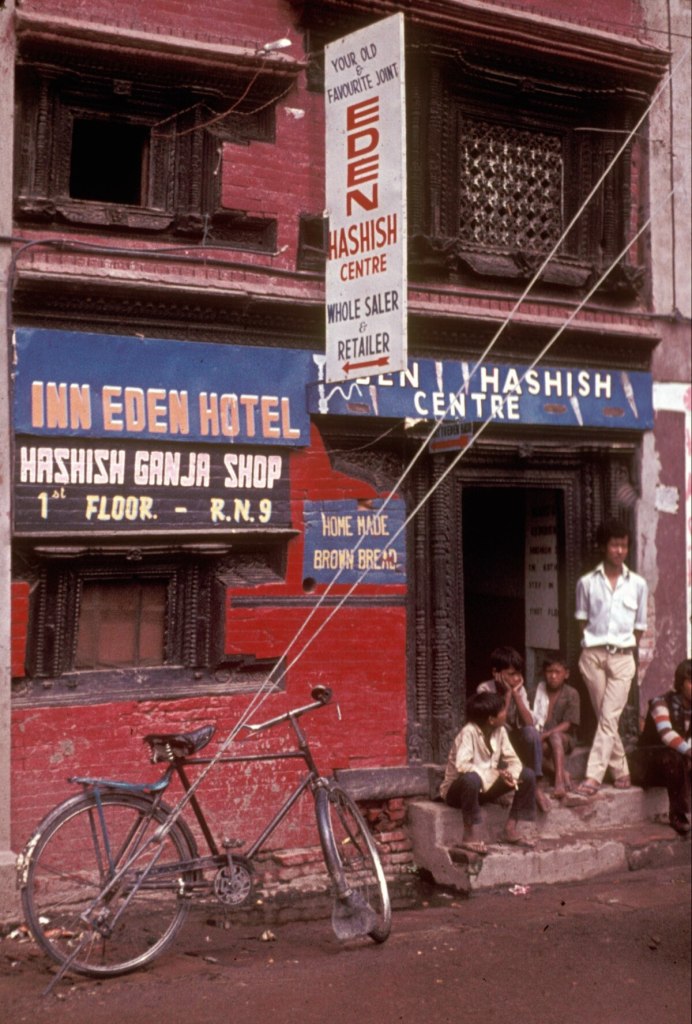

These early visitors weren’t tourists. They were pilgrims of the mind, in search of something sacred- Buddhism, hashish, or just silence. Nepal, newly open to foreigners, offered all three. The air was thin, the pace unhurried, and the boundaries between sacred and profane were blurry. Marijuana was not just legal- it was sold in government-licensed shops, alongside postcards, prayer beads, and colorful clothes. Kathmandubecame a quiet Eden, a Shangri-La in the Himalayas.

By the early 1970s, the whispers became a roar. It was this potent blend of the sacred and the remote that beckoned a new kind of traveler in the early 1970s. Kathmandu was the final stop on the Hippie Trail, a high-altitude utopia where marijuana was legal, the people were kind, and the soul could rest. They came in waves- on the Magic Bus, in VW vans, or simply by hitchhiking. They carried guitars, notebooks, dreams, and tales. In the quiet stillness of the Bagmati River or the echoing courtyards of Patan, many Westerners believed they had found what America’s cities and communes had promised but never delivered: a culture steeped in ritual, yet open to wanderers.

For the travelers, Kathmandu was cheap, welcoming, and otherworldly. Many wandered through the monasteries of Boudhanath and Swayambhu, quietly meditating with monks. Others found refuge in the temples of Pashupatinath, more enchanted than devout. In Bhaktapur and Patan, they painted, photographed, and sketched; mesmerized by the medieval architecture and the pace of life that felt untouched by time.

A few settled for weeks in the outskirts- Nagarkot, Pharping, and Shivapuri; camping under the stars in hilltops, reading Hesse and the Gita. They weren’t tourists- they were dwellers, they were seekers, drawn to ritual and reverie, chasing stillness through pujas and hashish haze, often blurring the line between reverence and indulgence.

Freak Street: The Epicenter of Hippies in Nepal.

At the center of it all was Freak Street- or Jhochhen Tole- a short strip of stone-paved road nestled just south of Kathmandu Durbar Square. What began as a quiet residential alley transformed, almost overnight, into a global crossroads of wanderers, mystics, artists, and seekers. Guesthouses sprouted up in ancient brick buildings, serving both as meeting places and refuges for those weary from their travels. They brought guitars, poetry, incense, and questions. In turn, they found a culture steeped in centuries of spirituality, hospitality, and patience. Not to mention, Nepal Hashish house was at the center of the it all.

On Freak Street, guitars mingled with Tibetan horns. German bakeries sprouted like mushrooms. Cafés served bhang-laced milk and hashish pancakes. Record players spun Dylan and Donovan under prayer flags. Here, you could trade your jeans for a homespun robe. Here, you could spend your afternoons reading Ginsberg or Rimbaud. And, as the sun dipped behind the temple rooftops you would find yourself invited to an impromptu sitar concert or one of numerous Bhajan sessions. For a time, Freak Street wasn’t just a place- it was an idea: freedom, escape, and the hope that somewhere between East and West, a new self might be born.

For a brief window in time, Nepal didn’t just host the global counterculture- it shaped its myth. Kathmandu became a meeting point between ancient ritual and Western rebellion, between spiritual tradition and psychedelic experimentation. It wasn’t always harmonious, but it was undeniably transformative. Kathmandu offered something profoundly different- space to breathe, reflect, and heal.

War on Drugs: The End of the Beginning and Garden Lost.

By the mid-1970s, the dream began to unravel. International pressure, particularly from the United States, forced the Nepali government to outlaw the production and sale of marijuana and hashish. The government-run hashish shops, symbols of Kathmandu’s permissiveness, were abruptly closed. Immigration tightened. Visa rules grew stricter. The cafés thinned out. The last Magic Buses turned around. Kathmandu’s days as a sanctuary for the global counterculture were over.

But something lingered. The hippies may have left Freak Street, but their footprints didn’t fade so easily. From guesthouses and trekking agencies to German bakeries and reggae bars, elements of that era still echo in today’s Thamel. The ethos of alternative living, global curiosity, and spiritual seeking survived, migrating from Jhochhen to Thamel, from hash pipes to hiking boots. Trekking replaced tripping. The Kathmandu Valley, once a canvas for psychedelic dreams, became a launchpad for commercial adventure. Nepal adapted- and moved on.

And yet, for those who remember or inherited the memory- the hippie era remains suspended in Kathmandu’s smoke-framed nostalgia. Freak Street was never just an idea, a place where the dreams of the 1960s could linger just a little longer, the imprint of which has never really faded. Through the 1980s and 90s, its influence echoed in Kathmandu’s bohemian corner cafes, a new generation of musicians and writers. Even today, when the tourists, more likely with trekking poles than tie-dye shirts, arrive, the spirit of those years survives in subtler ways: in Kathmandu’s tolerance for wanderers, its fusion of the sacred and the everyday.

Perhaps the garden was never meant to be found. But for a brief moment, Kathmandu felt like a place where it could almost be. The hippie movement didn’t change the world in the way its idealists had hoped. It didn’t end war or dismantle capitalism. But it left behind something that, perhaps, was even more valuable: the idea that a different world was possible. A world where love, music, and freedom were the ultimate expressions of life.

Leave a reply to sandeept252 Cancel reply